The Open Standards Board, which exists to make recommendations to the UK (Westminster) Government Cabinet Office, met last week and completed the journey to the first milestone in the new process by which open standards are to be selected. This process is based around the idea that “challenges” are raised on the Standards Hub, proposals worked up to meet challenges under the supervision of two panels (“data standards” and “technical standards”), and subsequently put before the Open Standards Board.

Author Archives: Adam Cooper

Report on a Survey of Analytics in Higher and Further Education (UK)

We have just published the results of an informal survey undertaken by Cetis to:

- Assess the current state of analytics in UK FE/HE.

- Identify the challenges and barriers to using analytics.

Learning Analytics Interoperability

The ease with which data can be transferred without loss of meaning from a store to an analytical tool – whether this tool is in the hands of a data scientist, a learning science researcher, a teacher, or a learner – and the ability of these users to select and apply a range of tools to data in formal and informal learning platforms are important factors in making learning analytics and educational data mining efficient and effective processes.

I have recently written a report that describes, in summary form, the findings of a survey into: a) the current state of awareness of, and research or development into, this problem of seamless data exchange between multiple software systems, and b) standards and pre-standardisation work that are candidates for use or experimentation. The coverage is, intentionally, fairly superficial but there are abundant references.

The paper is available in three formats: Open Office, PDF, MS Word. If printing, note that the layout is “letter” rather than A4.

Comments are very welcome since I intend to release an improved version in due course.

Open Standards Board and the Cabinet Office Standards Hub

Early last week the government announced the Open Standards Board had finally been convened via a press release from Francis Maude, the Minister for the Cabinet Office, and via a blog post from Liam Maxwell, the government’s Chief Technology Officer. This is a welcome development but what chuffed me most was that my application to be a Board member had been successful.

I say “finally” because it has taken quite a while for the process to move from a shadow board and a consultation on policy (Cetis provided feedback), through an extension of the consultation to allay fears of bias in a stakeholder event, analysis of the comments, publication of the final policy, and deciding on the role of the Open Standards Board. The time taken has been a little frustrating but I take comfort from my conclusion that these delays are signs of a serious approach, that this is not an empty gesture.

Before going on, I should publicly recognise the contribution of others that enabled me to make a successful application. Firstly: Jisc has provided the funding for Cetis and a series of supporters(*) for the idea of open standards in Jisc has kept the flame alive. Many years ago they had the vision and stuck with it in spite of wider scepticism, progress that has been often slow, a number of flawed standards (mistakes do happen), and the difficulty in assessing return on investment for activities that are essentially systemic in their effect. Secondly: my colleagues in Cetis from whom I have harvested wisdom and ideas and with whom I have shared revealing (and sometimes exhausting) debate. Looking back at what we did in the early 2000′s, I think we were quite naive but so was everyone else. I believe we now have much more sophisticated ideas about the process of standards-development and adoption, and of the kinds of interventions that work. I hope that is why I was successful in my application.

The Open Standards Board is concerned with open standards for government IT and is closely linked with actions dealing with Open Source Software and Open Data. All three of these are close to our hearts in Cetis and we hope both to contribute to their development (in government and the wider public sector) as well as helping there to be a bit more spill-over into the education system.

The public face of Cabinet Office open standards activity is the Standards Hub, which gives anyone the chance to nominate candidates to be addressed using open standards and to comment on the nominations of others. I believe this is the starting point for the business of the Board. The suggestions are bit of a mixed bag and the process is in need of more suggestions so – to quote the Hub website – if you know of an open standard that could be “applied consistently across the UK government to make our services better for users and to keep our costs down”, you know what to do!

The Open Standards Board has an interesting mix of members and I’m full of enthusiasm for what promises to be an exciting first meeting in early May.

—-

* – there are too many to mention but the people Cetis had most contact with include Tish Roberts, Sarah Porter and Rachel Bruce.

Analytics is Not New!

As we collectively climb up the hype cycle towards the peak of inflated expectations for analytics, and I think this can be argued for many industries and applications of analytics, a bit of historical perspective makes a good antidote both to exaggerated claims but also to the pessimists who would say it is “all just hype”.

That was my starting point for a paper I wrote towards the end of 2012 and which is now published as “A Brief History of Analytics“. As I did the desk research, three aspects recurred:

- much that appears recent can be traced back for decades;

- the techniques being employed by different communities of specialists are rather complementary;

- there is much that is not under the narrow spotlight of marketing hype and hyperbole.

The historical perspective gives us inspiration in the form of Florence Nightingale‘s pioneering work on using statistics and visualisation to address problems of health and sanitation and to make the case for change. It also reminds us that Operational Researchers (Operations Researchers) have been dealing with complex optimisation problems including taking account of human factors for decades.

I found that writing the paper helped me to clarify my thinking about what is feasible and plausible and what the likely kinds of success stories for analytics will be in the medium term. Most important, I think, is that our collective heritage of techniques for data analysis, visualisation and use to inform practical action shows that the future of analytics is a great deal richer than the next incarnation of Business Intelligence software or the application of predictive methods to Big Data. These have their place but there is more; analytics has many themes that combine to make it an interesting story that unfolds before us.

The paper “A Brief History of Analytics” is the ninth in the CETIS Analytics Series.

A Seasonal Sociogram for Learning Analytics Research

SoLAR, the Society for Learning Analytics Research has recently made available a dataset covering research publications in learning analytics and educational data mining and issued the LAK Data Challenge, challenging the community to use the dataset to answer the question:

What do analytics on learning analytics tell us? How can we make sense of this emerging field’s historical roots, current state, and future trends, based on how its members report and debate their research?

Thanks to too many repeats on the TV schedule I managed to re-learn a bit of novice-level SPARQL and manipulate the RDF/XML provided into a form I can handle with R.

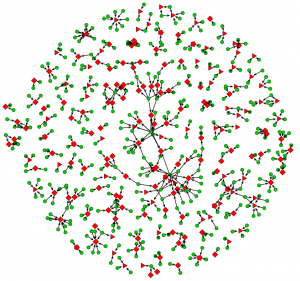

Now, I’ve had a bit of a pop at the sociograms – i.e. visualisations of social networks – in the past but they do have their uses and one of these is getting a feel for the shape of a dataset that deals with relations. In the case of the LAK challenge dataset, the relationship between authors and papers is such a case. So as part of thinking about whether I’m up for the approaching the challenge from this perspective it makes sense to visualise the data.

And with it being the Christmas season, the colour scheme chose itself.

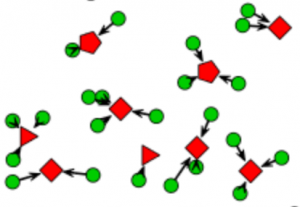

Paper Authorship for Proceedings from LAK, EDM and the JETS Special Edition on Learning and Knowledge Analytics (click on image for full-size version)

This is technically a “bipartite sociogram” since it shows two kinds of entity and relationships between types. In this case people are shown as green circles and papers shown as red polygons. The data has been limited to the conferences on Learning Analytics and Knowledge (LAK) 2011 and 2012 (red triangles) and the Educational Data Mining (EDM) Conference for the same years (red diamonds). The Journal of Educational Technology and Society special edition on learning and knowledge analytics was also published in 2012 (red pentagons). Thus, we have a snapshot of the main venues for scholarship vicinal to learning analytics.

So, what does it tell me?

My first observation is that there are a lot of papers that have been written by people who have written no others in the dataset for 2011/12(from now on, please assume I always mean this subset). I see this as being consistent with this being an emergent field of research. It is also clear that JETS attracted papers from people who were not already active in the field. This is not the entire story, however as the more connected central region of the diagram shows. Judging this region by eye and comparing it to the rest of the diagram, it looks like there is a tendency for LAK papers (triangles) to be under-represented in the more-connected region compared to EDM (diamonds). This is consistent with EDM conferences having been run since 2008 and their emergence from workshops on the Artificial Intelligence in Education. LAK, on the other hand began in 2011. Some proper statistics are needed to confirm judgement by eye. It would be interesting to look for signs of evolution following the 2013 season.

The sign of an established research group is the research group head who co-authors several papers with each paper having some less prolific co-authors who are working for the PhDs. The chief and Indians pattern. A careful inspection of the central region shows this pattern as well as groups with less evidence of hierarchy.

LAK came into being and attracted people without a great deal of knowledge of the prior existence of the EDM conference and community so some polarisation is to be expected. There clearly are people, even those with many publications, the have only published to one venue. Consistent with previous comments about the longer history of EDM it isn’t surprising that this is most clear for that venue since there are clearly established groups at work. What I think will be some comfort to the researchers in both camps who have made efforts to build bridges is that there are signs of integration (see the Chiefs and Indians snippet). Whether this is a sign of integrating communities or a consequence of individual preference alone is an open question. Another question to consider with more rigour and something to look out for in the 2013 season.

Am I any the wiser? Well… slightly, and it didn’t take long. There are certainly some questions that could be answered with further analysis and there are a few attributes not taken account of here, such as institutional affiliation or country/region. I will certainly have a go at using the techniques I outlined in a previous post if the weather is poor over the Christmas break but I think I will have to wait until the data for 2013 is available before some of the interesting evolutionary shape of EDM and LAK becomes accessible.

Merry Christmas!

Looking Inside the Box of Analytics and Business Intelligence Applications

To take technology and social process at face value is to risk failing to appreciate what they mean, do, and can do. Analytics and business intelligence applications or projects, in common with all technology supported innovations, are more likely to be successful if both technology and social spheres are better understood. I don’t mean to say that there is no room for intuition in such cases, rather that it is helpful to decide which aspects are best served by intuition or not and by whose intuition, if so. But how to do this?

Just looking can be a poor guide to understanding an existing application and just designing can be a poor approach to creating a new one. Some kind of method, some principles, some prompts or stimulus questions – I will use “framework” as an umbrella term – can all help to avoid a host of errors. Replication of existing approaches that may be obsolete or erroneous, falling into value or cognitive traps, failure to consider a wider range of possibilities, etc are errors we should try to avoid. There are, of course, many approaches to dealing with this problem other than a framework. Peer review and participative design have a clear role to play when adopting or implementing analytics and business intelligence but a framework can play a part alongside these social approaches as well as being useful to an individual sense-maker.

The culmination of my thinking about this kind of framework has just been published as the seventh paper in the CETIS Analytics Series, entitled “A Framework of Characteristics for Analytics“. This started out as a personal attempt to make sense of my own intuitive dissatisfaction with the traditions of business intelligence combined with concern that my discussions with colleagues about analytics were sometimes deeply at cross purposes or just unproductive because our mental models lacked sufficient detail and clarity to properly know what we were talking about or to really understand where our differences lay.

The following quotes from the paper.

A Framework of Characteristics for Analytics considers one way to explore similarities, differences, strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, etc of actual or proposed applications of analytics. It is a framework for asking questions about the high level decisions embedded within a given application of analytics and assessing the match to real world concerns. The Framework of Characteristics is not a technical framework.

This is not an introduction to analytics; rather it is aimed at strategists and innovators in post-compulsory education sector who have appreciated the potential for analytics in their organisation and who are considering commissioning or procuring an analytics service or system that is fit for their own context.

The framework is conceived for two kinds of use:

- Exploring the underlying features and generally-implicit assumptions in existing applications of analytics. In this case, the aim might be to better comprehend the state of the art in analytics and the relevance of analytics methods from other industries, or to inspect candidates for procurement with greater rigour.

- Considering how to make the transition from a desire to target an issue in a more analytical way to a high level description of a pilot to reach the target. In this case, the framework provides a starting-point template for the production of a design rationale in an analytics project, whether in-house or commissioned. Alternatively it might lead to a conclusion that significant problems might arise in targeting the issue with analytics.

In both of these cases, the framework is an aid to clarify or expose assumptions and so to help its user challenge or confirm them.

I look forward to any comments that might help to improve the framework.

What does “Analytics” Mean? (or is it just another vacuuous buzz word?)

“Analytics” certainly is a buzz word in the business world and almost impossible to avoid at any venue where the relationship between technology and post-compulsory education is discussed, from bums-on-seats to MOOCs. We do bandy words like analytics or cloud computing around rather freely and it is so often the case with technology-related hype words that they are used by sellers of snake oil or old rope to confuse the ignorant and by the careless to refer vaguely to something that seems to be important.

Cloud computing is a good example. While it is an occasionally useful umbrella term for a range of technologies, techniques and IT service business models, it masks differences that matter in practice. Any useful thinking about cloud must work on a more clear understanding of the kinds of cloud computing service delivery level and the match to the problem to be solved. To understand the very real benefits of cloud computing, you need to understand the distinct offerings; any discussion that just refers to cloud computing is likely to be vacuuous. These distinctions are discussed in a CETIS briefing paper on cloud computing.

But is analytics like cloud computing, is the word itself useful? Can a useful and clear meaning, or even a definition, of analytics be determined?

I believe the answer is “yes” and the latest paper in our Analytics Series, which is entitled “What is Analytics? Definition and Essential Characteristics” explores the background and discusses previous work on defining analytics before proposing a definition. It then extends this to a consideration of what it means to be analytical as opposed to being just quantitative. I realise that the snake oil and old rope salesmen will not be interested in this distinction; it is essentially a stance against uncritical use of “analytics”.

There is another way in which I believe the umbrella terms of cloud computing and analytics differ. Whereas cloud computing becomes meaningful by breaking it down and using terms such as “software as a service”, I am not convinced that a similar approach is applicable to analytics. The explanation for this may be that cloud computing is bound to hardware and software, around which different business models become viable, whereas analytics is foremost about decisions, activity and process.

Terms for kinds of analytics, such as “learning analytics”, may be useful to identify the kind of analytics that a particular community is doing but to define such terms is probably counter-productive (although working definitions may be very useful to allow the term to be used in written or oral communications). One of the problems with definitions is the boundaries they draw. Where would learning analytics and business analytics have boundary in an educational establishment? We could probably agree that some cases of analytics were on one side or the other but not all cases. Furthermore, analytics is a developing field that certainly has not covered all that is possible and is very immature in many industries and public sector bodies. This is likely to mean revision of definitions is necessary, which rather defeats the object.

Even the use of nouns, necessary though it may be in some circumstances, can be problematical. If we both say “learning analytics”, are we talking about the same thing? Probably not, because we are not really talking about a thing but about processes and practices. There is a danger that newcomers to something described as “learning analytics” will construct quite a narrow view of “learning analytics is ….” and later declaim that learning analytics doesn’t work or that learning analytics is no good because it cannot solve problem X or Y. Such blinkered sweeping statements are a warning sign that opportunities will be missed.

Rather than say what business analytics, learning analytics, research analytics, etc is, I think we should focus on the applications, the questions and the people who care about these things. In other words, we should think about what analytics can and cannot help us with, what it is for, etc. This is reflected in most of the titles in the CETIS Analytics Series, for example our recently-published paper entitled “Analytics for Learning and Teaching“. The point being made about avoiding definitions of kinds of analytics is expanded upon in “What is Analytics? Definition and Essential Characteristics“.

The full set of papers in the series is available from the CETIS Publications site.

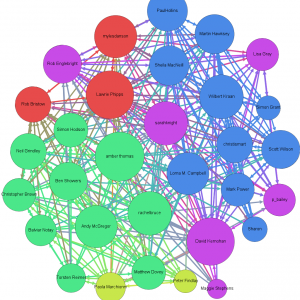

Modelling Social Networks

Social network analysis has become rather popular over the last five (or so) years; the proliferation of different manifestations of the social web has propelled it from being a relatively esoteric method in the social sciences to become something that has touched many people, if only superficially. The network visualisation – not necessarily a social network, e.g. Chris Harrison’s internet map – has become a symbol of the transformation in connectivity and modes of interaction that modern hardware, software and infrastructure has brought.

This is all very well, but I want more than network visualisations and computed statistics such as network density or betweenness centrality. The alluring visualisation that is the sociogram tends to leave me rather non-plussed.

Now, don’t get me wrong: I’m not against this stuff and I’m not attacking the impressive work of people like Martin Hawksey or Tony Hirst, the usefulness of tools like SNAPP or recent work on the Open University (UK) SocialLearn data using the NAT tool. I just want more and I want an approach which opens up the possibility of model building and testing, of hypothesis testing, etc. I want to be able to do this to make more sense of the data.

Warning: this article assumes familiarity with Social Network Analysis.

Tools and Method

Several months ago, I became rather excited to find that exactly this kind of approach – social network modelling – has been a productive area of social science research and algorithm development for several years and that there is now a quite mature package called “ergm” for R. This package allows its user to propose a model for small-scale social processes and to evaluate the degree of fit to an observed social network. The mathematical formulation involves an exponential to calculate probability hence the approach is known as “Exponential Random Graph Models” (ERGM). The word “random” captures the idea that the actual social network is only one of many possibilities that could emerge from the same social forces, processes, etc and that this randomness is captured in the method.

I have added some what I have found to be the most useful papers and a related book to a Mendeley group; please consult these for an outline of the historical development of the ERGM method and for articles introducing the R package.

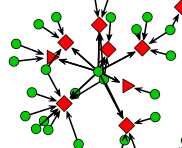

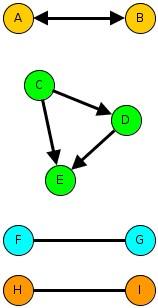

The essential idea is quite simple, although the algorithms required to turn it into a reality are quite scary (and I don’t pretend to understand enough to do proper research using the method). The idea is to think about some arguable and real-world social phenomena at a small scale and to compute what weightings apply to each of these on the basis of a match between simulations of the overall networks that could emerge from these small-scale phenomena and a given observed network. Each of the small-scale phenomena must be expressed in a way that a statistic can be evaluated for it and this means it must be formulated as a sub-graph that can be counted.

The diagram above illustrates three kinds of sub-graph that match three different kinds of evolutionary force on an emerging network. Imagine the arrows indicate something like “I consider them my friend”, although we can use the same formalism for less personal kinds of tie such as “I rely on” or even the relation between people and resources.

- The idea of mutuality is captured by the reciprocal relationships between A and B. Real friendship networks should be high in mutuality whereas workplace social networks may be less mutual.

- The idea of transitivity is captured in the C-D-E triangle. This might be expressed as “my friend’s friend is my friend”.

- The idea of homophily is captured in the bottom pair of subgraphs, which show preference for ties to the same colour of person. Colour represents any kind of attribute, maybe a racial label for studies of community polarisation or maybe gender, degree subject, football team… This might be captured as “birds of a feather fly together”.

One of the interesting possibilities of social network modelling is that it may be able to discover the likely role of different social processes, which we cannot directly test, with qualitatively similar outcomes. For example, both homophily and transitivity favour the formation of cohesive groups. A full description of research using ERGMs to deal with this kind of question is “Birds of a Feather, or Friend of a Friend? Using Exponential Random Graph Models to Investigate Adolescent Social Networks” (Goodreau, Kitts & Morris): see the Mendeley group.

A First Experiment

In the spirit of active learning, I wanted to have a go. This meant using relatively easily-available data about a community that I knew fairly well. Twitter follower networks are fashionable and not too hard to get, although the API is a bit limiting, so I wrote some R to crawl follower/friends and create a suitable data structure for use with the ERGM package.

Several evenings later I concluded that a network defined as followers of the EC-TEL 2012 conference was unsuitable. The problem seems to be that the network is not at all homogeneous while at the same time there are essentially no useful person attributes to use; the location data is useless and the number of tweets is not a good indicator of anything. Without some quantitative or categorical attribute you are forced to use models that assume homogeneity. Hence nothing I tried was a sensible fit.

Lesson learned: knowledge of person (vertex) attributes is likely to be important.

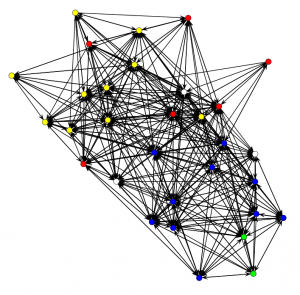

My second attempt was to consider the Twitter network between CETIS staff and colleagues in the JISC Innovation Group. In this case, I know how to assign one attribute that might be significant: team membership.

Without looking at the data, it seems reasonable to hypothesise as follows:

- We might expect a high density network since:

- Following in Twitter is not an indication of a strong tie; it is a low cost action and one that may well persist due to a failure to un-follow.

- All of the people involved work directly or indirectly (CETIS) for JISC and within the same unit so we might expect.

- We might expect a high degree of mutuality since this is a professional peer network in a university/college setting.

- The setting and the nature of Twitter may lead to a network that does not follow organisational hierarchy.

- We might expect teams to form clusters with more in-team ties than out-of-team ties. i.e. a homphily effect.

- There is no reason to believe any team will be more sociable than another.

- Since CETIS was created primarily to support the eLearning Team we might expect there to be a preferential mixing-effect.

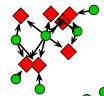

CETIS and JISC Innovation Group Twitter follower network. Colours indicate the team and arrows show the "follows" relationship in the direction of the arrow.

Nonplussed? What of the hypotheses?

Well… I suppose it is possible to assert that this is quite a dense network that seems to show a lot of mutuality and, assuming the Fruchterman-Reingold layout algorithm hasn’t distorted reality, which shows some hints at team cohesiveness and a few less-connected individuals. I think JISC management should be quite happy with the implications of this picture, although it should be noted that there are some people who do not use Twitter and that this says nothing about what Twitter mediates.

A little more attention to the visualisation can reveal a little more. The graph below (which is a link to a full-size image) was created using Gephi with nodes coloured according to team again but now sized according to the eigenvector centrality measure (area proportional to centrality), which gives an indication of the influence of that person’s communications within the given network.

Visualising the CETIS and JISC Innovation network with centrality measures. The author is among those who do not tweet.

This does, at least, indicate who is most, least and middling in centrality. Since I know most of these people, I can confirm there are no surprises.

Trying out several candidate models in order to try to decide on the previously enumerated hypotheses (and some others omitted for brevity) leads to the following tentative conclusions, i.e. to a model that appeared to be consistent with the observed network. “Appeared to be consistent” means that my inexperienced eye considered that there was acceptable goodness of fit between a range of statistics computed on the observed network and ensembles of networks simulated using the given model and best-fit parameters.

Keeping the same numbering as the hypotheses:

- ERGM isn’t needed to judge network density but the method does show the degree to which connections can adequately be put down to pure chance.

- There is indeed a large positive coefficient for mutuality, i.e. that reciprocal “follows” are not just a consequence of chance in a relatively dense network.

- It is not possible to make conclusions about organisational hierarchy.

- There is a statistically significant greater density within teams. i.e. team homophily seems to be affecting the network. This seems to be strongest for the Digital Infrastructure team, then CETIS then the eLearning team but the standard errors are too large to claim this with confidence. The two other teams were considered too small to draw a conclusion

- None of CETIS, the eLearning team or the Digital Infrastructure team seem to be more sociable. The two other teams were considered too small to draw a conclusion. This is known as a “main effect”.

- There is no statistically significant preference for certain teams to follow each other. In the particular case of CETIS, this makes sense to an insider since we have worked closely with JISC colleagues across several teams.

One factor that was not previously mentioned but which turned out to be critical to getting the model to fit was individual effects. Not everyone is the same. This is the same issue as was outlined for the EC-TEL 2012 followers: heterogeneity. In the present case, however, only a minority of people stand out sufficiently to require individual-level treatment and so it is reasonable to say that, while these are necessary for goodness of fit, they are adjustments. To be specific, there were four people who were less likely to follow and another four who were less likely to be followed. I will not reveal the names but suffice to say that, surprising though the results was at first, it is explainable for the people in CETIS.

A Technical Note

This is largely for anyone who might play with the R package. The Twitter rules prevent me from distributing the data but I am happy to assist anyone wishing to experiment (I can provide csv files of nodes and edges, a .RData file containing a network object suitable for use with the ERGM package or the Gephi file to match the picture above).

The final model I settled on was:

twitter.net ~ edges +

sender(base=c(-4,-21,-29,-31)) +

receiver(base=c(-14,-19,-23,-28)) +

nodematch("team", diff=TRUE, keep=c(1,3,4)) +

mutual

This means:

- edges = > the random chance that A follows B unconditionally on anything.

- sender => only these four vertices are given special treatment in terms of their propensity to follow.

- receiver => special treatment for propensity to be followed.

- nodematch => consider the team attribute for teams 1, 3 and 4 and use a different parameter for each team separately (i.e. differential homophily).

- mutual => the propensity for a person to reciprocate being followed.

And for completeness the estimated model parameters for my last run. The parameter for “edges” indicates the baseline random chance and, if the other model elements are ignored, an estimate of -1.64 indicates that there is about a 16% chance of a randomly chosen A->B tie being present (the estimate = logit(p)). The interpretation of the other parameters is non-trivial but in general terms, a randomly chosen network containing a higher value statistic for a given sub-graph type will be more probable than one containing a lower value when the estimated parameter is positive and less probable when it is negative. The parameters are estimated such that the observed network has the maximum likelihood according to the model chosen.

Estimate Std. Error MCMC % p-value edges -1.6436 0.1580 1 < 1e-04 *** sender4 -1.4609 0.4860 2 0.002721 ** sender21 -0.7749 0.4010 0 0.053583 . sender29 -1.9641 0.5387 0 0.000281 *** sender31 -1.5191 0.4897 0 0.001982 ** receiver14 -2.9072 0.7394 9 < 1e-04 *** receiver19 -1.3007 0.4506 0 0.003983 ** receiver23 -2.5929 0.5776 0 < 1e-04 *** receiver28 -2.5625 0.6191 0 < 1e-04 *** nodematch.team.CETIS 1.9119 0.3049 0 < 1e-04 *** nodematch.team.DI 2.6977 0.9710 1 0.005577 ** nodematch.team.eLearning 1.1195 0.4271 1 0.008901 ** mutual 3.7081 0.2966 2 < 1e-04 *** --- Signif. codes: 0 ‘***’ 0.001 ‘**’ 0.01 ‘*’ 0.05 ‘.’ 0.1 ‘ ’ 1

Outlook

The point of this was a learning experience; so what did I learn?

- It does seem to work!

- Size is an issue. Depending on the model used, a 30 node network can take several tens of seconds to either determine the best fit parameters or to fail to converge.

- Checking goodness of fit is not simple; the parameters for a proposed model are only determined for the statistics that are in the model and so goodness of fit testing requires consideration of other parameters. This can come down to “doing it by eye” with various plots.

- Proper use should involve some experimental design to make sure that useful attributes are available and that the network is properly sampled if not determined a-priori.

- There are some pathologies in the algorithms with certain kinds of model. These are documented in the literature but still require care.

The outlook, as I see it, is promising but the approach is far from being ready for “real users” in a learning analytics context. In the near term I can, however, see this being applied by organisations whose business involves social learning and as a learning science tool. In short: this is a research tool that is worthy of wider application.

This is an extended description of a lightning talk given at the inaugural SoLAR Flare UK event held on November 19th 2012. It may contain errors and omissions.

Open Source and Open Standards in the Public Sector

Yesterday I attended day 1 of a conference entitled “Public Sector: Open Source” and, while Open Source Software (OSS) was the primary subject, Open Standards were very much on the agenda. I went in particular because of an interest in what the UK Government Cabinet Office is doing in this area.

I have previously been quite positive about both the information principles and the open standards consultation (blog posts here and here respectively). We provided a response to the consultation and were pleased to see the Nov 1st announcement that government bodies must comply with a set of open standards principles.

The speaker from the Cabinet Office was Tariq Rashid (IT Reform group) and we were treated to a quite candid assessment of the challanges faced by government IT, with particular reference to OSS. His assessment of the issues and how to deal with them was cogent and believable, if also a little scary.

Here are a few of the things that caught my attention.

Outsource the Brawn not the Brain

Over a period of many years the supply of well-informed and deeply technical capability in government has been depleted such that too many decisions are made without there being an appropriate “intelligent customer“. To quote Tariq: “we shouldn’t be spending money unless we know what the alternatives are.” The particular point being made was about OSS alternatives – and they have produced an Open Source Procurement Toolkit to challenge myths and to guide people to alternatives – but the same line of argument extends to there being a poor understanding of the sources of technical lock-in (as opposed to commercial lock-in) and how chains of dependency could introduce inertia through decisions that are innocuous from a naive analysis.

By my analysis, the Cabinet Office IT reform team are the exception that proves the general point. It is also a point that universities and colleges should be wary of as their senior management tries to cut out “expensive people we don’t really need”.

The Current Procurement Approach is Pathological

There is something slightly ironic that it takes a Tory government to seriously attack an approach which sees the greatest fraction of the incredible £21 billion p.a. central government spend on IT go to a handful of big IT houses (yes, countable on 2 hands).

In short: the procurement approach, which typically involves a large amount of bundling-up, reduces competition and inhibits SMEs and providers of innovative solutions as well as blocking more agile approaches.

At the intersection between procurement approach and brain-outsourcing is the critical issue that the IT that is usually acquired lacks a long term view of architecture; this becomes reduced to the scope of tendered work and build around the benefits of the supplier.

Emphasis on Procurement

Most of the presentations placed most emphasis on the benefits of OSS in terms of procurement and cost and this was a central theme of Tariq’s talk also. Having spent long enough consorting with OSS-heads I found this to be rather narrow. What, for example, about the opportunities for public sector bodies to engage in acts of co-creation, either to lead or significantly contribute to OSS projects. There are many examples of commercial entities making significant investments in developer salaries while taking a hands-off approach to governance of the open source product (e.g. IBM and the eclipse platform).

For now, it seems, this kind of engagement is one step ahead of what is feasible in central government; there is a need for thinking to move on, to mature, from where it is now. I also suspect that there is plenty of low-hanging fruit – easy cases to make for cost savings in the near term – whereas co-creation is a longer term strategy. Tariq added that it might be only 2-3 years before government was ready to begin making direct contributions to LibreOffice, which is already being trialled in some departments.

Another of the speakers, representing sambruk (one of the partners in OSEPA, the project that organised the conference) seems to be heading towards more of a consortium model that could lead to something akin to the Sakai or Kuali model for Swedish municipality administration.

Conclusion

For all the Cabinet Office has a fairly small budget, its gatekeeper role – it must approve all spending proposals over £5 million and has some good examples of having prompted significant savings (e.g. £12 -> £2 million on a UK Borders procurement) – makes it a force to be reckoned with. Coupled with an attitude (as I perceive it) of wanting to understand the options and best current thinking on topics such as open source and open standards, this makes for a potent force in changing government IT.

The challenge for universities and colleges is to effect the same kind of transformation without an equivalent to the Cabinet Office and in the face of sector fragmentation (and, at best, some fairly loose alliances of sovereign city states).