The JLeRN experiment was a toe dipped in the learning registry, a trial at different approach to sharing information about learning resources and how they are used that focusses on getting the information out there and not on worrying over the schemas and formats in which the information is conveyed. That experiment (JLeRN, not the Learning Registry as a whole) is drawing to a close, so we had a meeting earlier this week to review what had been done, what had been learnt and what was left to do and learn.

Sarah Currier had arranged for projects that had worked with JLeRN blog something about what they had done before the meeting, here’s the email with a summary of them, if you haven’t come across JLeRN before you might want to have a look through them before reading on. What I want to describe here is my own understanding of where the Learning Registry is and to report some of the issues about it raised at the meeting.

The Learning Registry: Nodes or a network?

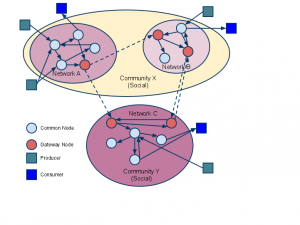

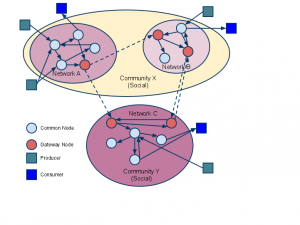

The learning registry as a network from a presentation by Dan Rehak and others.. © Copyright 2011 US Advanced Distributed Learning Initiative: CC-BY-3.0.

From the outset the Learning Registry was conceived as a network, the software created would be nodes that connected together to share data about resources. Some of the details have been put on the back burner since those early descriptions, for example the ideas of communities and gateway nodes haven’t been much developed.

The community map on the Learning Registry website shows three nodes (the red pins), including the JLeRN node; Steve Midgely told us via email “There are a few development nodes out there that we know of: Agilix, Illinois Dept of Commerce and California Dept of Ed. To my knowledge there are no production nodes beyond the ones we currently run. Several companies have expressed interest in taking over our production nodes including Dell, Cisco and Amazon.” To that tally I can add the EngRich node at Liverpool. Steve adds that the only network he knows of is the LR public network. Now, I’m not sure about the other nodes, but I do know that the JLeRN and EngRich nodes haven’t interacted with the public network in any meaningful way (yet).

So I think we have to say that, to date, there isn’t really much to prove the concept of the Learning Registry as a network. There are, however some developments in the works that I think will change that, for example the Learning Registry Index, see below.

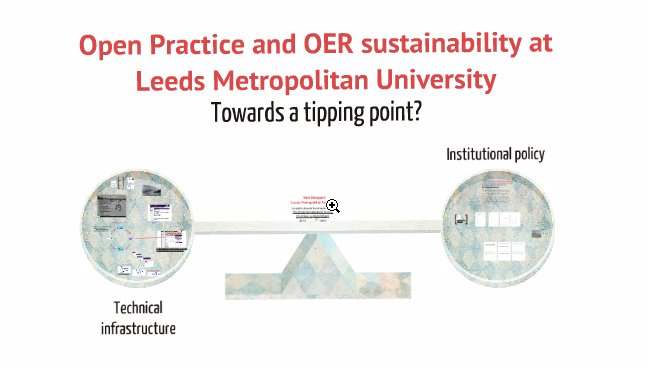

Services

The other aspect of the development of the Learning Registry against the vision shown in the diagram above is that of services being built to interact with the data in the nodes (these are shown as square in the diagram above). This is crucial since the Learning Registry is no more than plumbing to shift data around, it does nothing with that data that would interest a teacher or learner. It is left to others to develop services that meet user needs–Pat Lockley summed this up quite nicely in his presentation showing how the learning registry was targeted at developers and promoted relationships between developers, service managers and users more than was the case with traditional repository software.

“I think the major point of my slides was to suggest the learning registry is a “developer’s repository” – not that you need a developer to use it, more that you develop services around a node. Also, I feel there is a greater role for the developer in the ecosystems around a node than around a repository – the services on offer, and the scope of services you create seem richer – partially as any data can be stored.”

Well, there are some services for getting data in, there is the OAI-PMH to Learning Registry Publish Utility, and there is Pat’s RSS importer, Ramanathan, and his Google analytics data importer, Pliny. Also at least two projects–Scott Wilson’s SPAWS and Liverpool University’s EngRich–had involved the submission of data to Learning Registry nodes as part of the services they created.

But putting data in is meeting a service manager’s needs, it’s no good in itself since it doesn’t meet any user needs. There are a few user oriented services built off data in the Learning Registry. Pat showed us a couple of Chrome plugins, demos here and here. These are great as proofs of concept, and really important as such, they help show non-technical people what the learning registry is for. But there then follows some expectation management while you explain the limitations of the demonstrators. Other projects had embedded means of getting data out of the Learning Registry nodes into their project outputs, for example EngRich have an iLike widget for the Liverpool student portal that shows what resources students on specific courses have recommended based on data in their Learning Registry node.

Steve Midgely provided us with some very promising information, “the Gates foundation is funding several groups to build index and search services on top of Learning Registry (called Learning Registry Index) and that will require running nodes of some kind.”

Does it work?

One message that I picked up during the meeting and elsewhere is that the Learning Registry, as software, works. The people who set up nodes seem to have done so quickly, the people who used the APIs didn’t report problems in doing so. That’s a good place to be starting.

At a deeper level I guess we need to wait until there are more services built off the data in the Learning Registry to find out whether the Learning Registry works as a concept. Some known problems have been deliberately pushed out of scope in the development of the Learning Registry, one key one is not worrying about what formats and schemas for the data that goes in. This is good if you are submitting data, but unless some level of agreement is reached it does place the onus for making sense of the data on the people who are creating services that use the data. So far, the extent to which this (reaching agreement or making sense of arbitrary data) is possible in the context of the Learning Registry is untested.

Other questions remain over how the learning registry will function as a network, for example how duplicate and complementary records about the same resource will be dealt with when many people might be providing information about the same resource.

Why use it?

Owen Stephens and David Kay were at the meeting asking some very pertinent questions. Neither are particularly caught up in the education technology world, with more of a background in information systems for libraries, where of course there are different approaches to solving similar problems. So, why use the Learning Registry rather than raw couchDB, or some other schemaless, NoSQL, document store (e.g. MongoDB, which is popular for research data management), or free text indexing and search software such as Lucene/Solr, or RDF triple stores, or just a traditional relational database with SQL? To some extent the aim at the moment is to try and answer some of those questions: we won’t know if we don’t try it. But it’s valid to ask how far have we got to answering them, and here is my appraisal.

RDF?

Schemaless sharing of data still appeals to me because I don’t think we know what schema we want to use to share some of the interesting information about the use of resources for teaching and learning. I think the RDF approach will influence the data that is submitted, for example there is interest in using the Learning Registry to store LRMI style metadata. LRMI is adding properties to schema.org so that educational characteristics of resources can be described, and schema.org is only a step or two away from semantic web approaches such as RDF. But some influences of RDF we don’t want. For example there is a tendency at times for RDF approaches to fixate on ontologies. That would stall us. So, for example in LRMI it is possible to say that a resource “aligns” with some point in an educational framework: i.e. it is useful for teaching some topic in a standard curriculum, or assessing some skill required by a competency framework. That’s really useful, but the vocabulary for the nature of the alignment has had to be left open (“teaches” and “assess” are two suggested terms, others are that the resource has a certain “text complexity” or requires a “reading level” or other “educational level”)–the understanding of what education is about varies so much over the world and between settings that agreement on a closed ontology seems unattainable. Still, you could use RDF if you didn’t specify and ontology, and if you could make sense of the RDF without one.

Another weakness of RDF in this context, as I understand it, is its ability to deal with subjective opinions. As soon as a teacher or learner sees an assertion that resource X is good for teaching topic Y (to continue the example used above) they should be asking “says who”. Engineering students at Liverpool are more interested in what other Engineering students find useful, especially those at Liverpool, than they are in the opinions of physics students. Yes, you can have named graphs in RDF and provide information about who asserted which triples, but it goes beyond what is usual, whereas in it is built in from the start in the Learning Registry concept of paradata.

All of that is somewhat conjectural though, because as yet there is little in the Learning Registry that is not metadata that could be expressed in some standard schema such as LOM XML or DC RDF.

Other schemaless data stores

Why not use just CouchDB, without the Learning Registry API, or MongoDB, or Lucene? All of these would make sense for single instance data stores, which is pretty much what we have now with single more-or-less isolated nodes rather than a network. And, yes, I am sure that some way of sharing data between them could be worked up if that is what you wanted. So again any advantages of the Learning Registry is still putative at this stage.

One advantage of the Learning Registry is that, as I mentioned above, it does seem to work: it does seem to come out of the package as a functional way of storing and sharing data that is tailored to education. So as an introduction to No SQL databases it’s not a bad place for the education community to start.

In summary

In a post about the end of the JLeRN project David Kay has quoted Simon Schama on his not being sure whether the French Revolution was over. I’ll quote what Chairmain Mao supposedly said when asked what he thought of the French Revolution; “it’s too early to tell”. The things to look out for are a functioning network of nodes and user-facing services being delivered from data in those nodes. Then we can ask whether that data could be shared in any other way. For the time being I think that the main achievement of JLeRN and the UK’s involvement in the Learning Registry is that it has started people thinking about alternatives to relational databases and they have taken first steps into working with these. Too often, I think, data has been squeezed into an relational data where the benefits of doing so are simply that it is what the developer happens to be familiar with. If all you have is a hammer then you can have real problems dealing with screws.

[updated to correct an attribution error as to who was comparing JLeRN to the French revolution]

(By: Nick Sheppard, Leeds Metropolitan University)

(By: Nick Sheppard, Leeds Metropolitan University)