From UCAS applications to HESA returns, and from league tables to the academic technology approval scheme, degree programmes and modules are classified by subject. JACS3 does that job now, but HECoS will do it in the future. Here are the main differences.

After many years of use, the Joint Academic Coding System (JACS) that’s pervasive in UK Higher Education data sets ran into some limits: it was running out of codes in some subject areas, and it was being used for many more purposes than it was originally designed to support.

That’s why the Higher Education Data and Information Improvement Programme (HEDIIP) commissioned CETIS, in collaboration with APS and Aspire, to consult with the sector on a replacement of the vocabulary. The result of that work is the Higher Education Coding of Subjects (HECoS) vocabulary. HECoS has now reached the penultimate stage in that a release candidate is out for consultation, as are proposals for the governance and adoption of the scheme.

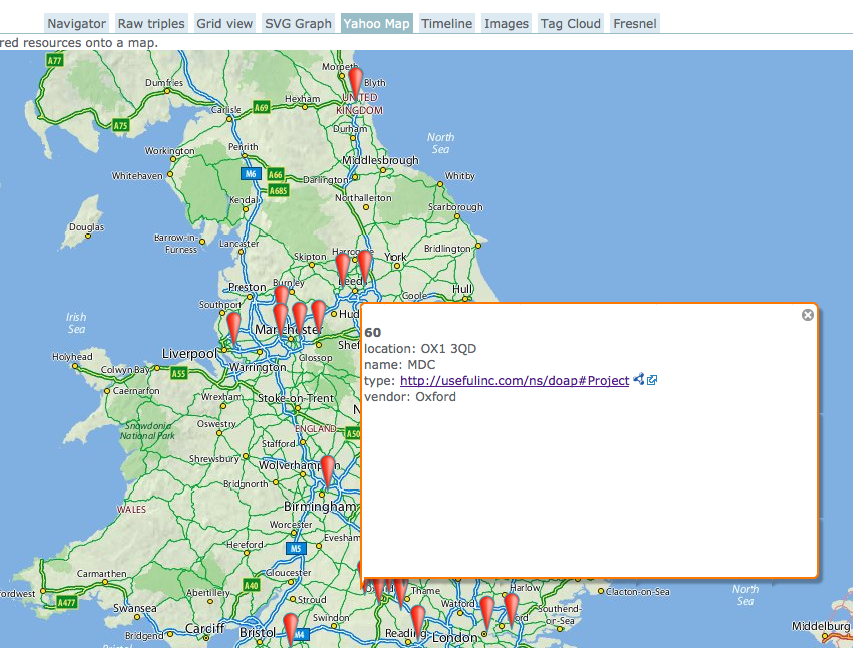

The whole vocabulary can be seen on our tematres development site, and reports on the development of HECoS, as well as the proposals for governance and adoption are available from the consultation site.

Here are the main differences between JACS3 and HECoS in a nutshell, though;

One flat list, no hierarchies, and no memorable codes

This is easily the biggest and most noticeable change. HECoS itself is just a list of terms without any implied or given groupings. That doesn’t mean groupings and hierarchies aren’t important, quite the contrary: different organisations have different uses for subject information, and that means they can group subjects differently.

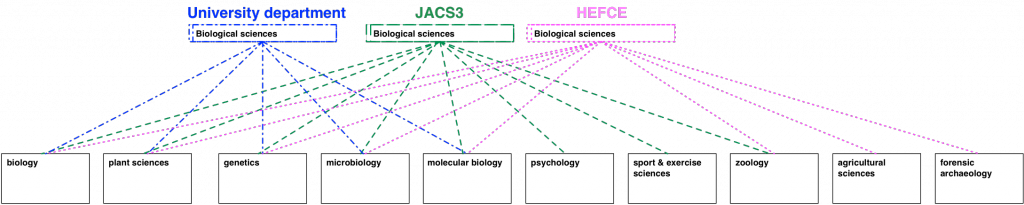

In a way, that follows on from what’s already happening with JACS3 in practice. The definition of what subjects constitutes biological sciences, for example, already differs between JACS3, HEFCE and what a typical university is likely to be able to offer. Different drivers and different contexts lead these organisations to group subjects differently, and HECoS is designed to enable different groupings to exist side by side, whilst still sharing the same subject terms.

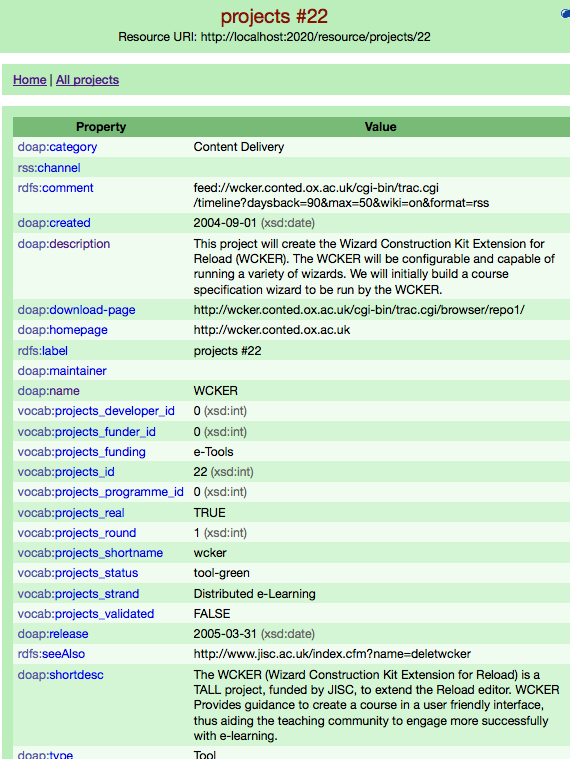

A consequence of the approach is that the familiar JACS3 codes (“L3xx” is anything sociological etc.) are no longer valid. From the perspective of HECoS “sociolinguistics” will therefore have no defined link with “sociology”, which is why the code for the former is “101016” –or a URI that encodes that number such as http://hecos.hediip.ac.uk/terms/101016– and the code for the latter is “100505”.

For ease of navigation, however, HECoS will come with some common groupings. There is a “sociology group” that has both “sociolinguistics” and “sociology” in it. This is just to help people find terms, and nodes like “sociology group” cannot be used to classify a degree programme or module.

Terms are based on demonstrated use, need and distinguishability

While JACS was reviewed periodically, it hasn’t always had formal acceptance criteria either for the terms that were already in there, or for newly proposed ones. HECoS does have a proposal for it, which has already been applied in the development of the current draft.

The criteria for the first cut were, in short:

- is the term in JACS3?

- is there evidence of use of the term in HESA data returns?

- is the term’s definition and scope sufficiently clear and comprehensive to allow classification?

- is the term reliably distinguishable from other terms?

The first criterion comes out of a recognition that JACS has imposed a structure and created its own reality over the years. That’s a good thing, and worth preserving for time series analysis reasons alone. The second criterion addresses an issue that has bedevilled JACS for a while: many terms were sound in theory, but barely or never used in practice. This creates confusion and often makes coding unreliable: what good is a term if it groups one degree programme in one institution? For that reason, we looked at whether a term has at least two degree programmes in at least two institutions in HESA student data returns.

The third criterion has to do with the way some JACS terms were defined: some were incomplete –e.g. “history by topic” without specifying what that topic was– or where not sufficiently complete to determine what was in or out. The final criterion of distinguishability is related to that: we examined the HESA returns for consistency of coding. If the spread of similar degree programmes over several terms indicated that people were struggling to distinguish between terms, we’ve rearranged terms so that they follow the groupings that were obvious in the data as closely as possible. We’ve also started to test any such changes with sorting exercises to ensure that people can indeed distinguish between four related terms.

A commonly administered change process

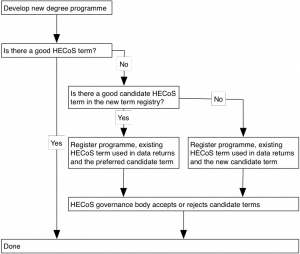

Just like JACS evolved over the years, so will HECoS. The difference is that we are proposing to regularise the change and allow it to follow a predictable path. The main mechanism for that would be a registry for new terms. The diagram outlines how a new subject term can be discovered, or entered for consideration for inclusion, or discovery by others.

The proposed criteria for accepting a new term into HECoS proper are similar the ones used for the first draft: a term has to be demonstrably in use, or fill a need, and be distinguishable by non-specialists. In each case, though, the HECoS governance body, which is designed to represent the whole sector, will have the ultimate say on which terms will be accepted or retired, and how often these changes will happen.