(14th in my logic of competence series)

Earlier this week I was at a meeting where we were talking about interoperability for abilities, and there was much discussion about the niceties of representation. Human readability is significant — whether the representation reflects what is in people’s minds. The same logic can be represented in radically different ways that are still logically equivalent (and so interoperable); there remains the question of what is identified by identifiers.

A relatively well-known example of variation of readability between different representations involves RDF. RDF/XML has a tendency to make people run a mile, as it can be difficult to comprehend what is represented. Triples formats (e.g. Turtle) at least have a great simplicity to them, because you can see clearly the mapping between the triples and the RDF “graph” (of blobs and arrows) that represents your little corner of the Semantic Web. (I am one of those who only started to appreciate RDF after getting over RDF/XML.) The problem with triples formats is that the knowledge structure is finely fragmented, so you don’t get a clear overview from the triples of what is being expressed: you still need a diagram that represents that overall structure. This is not a surprise — it is generally very hard to serialise a network structure in a comprehensible way. Only particular forms lend themselves to serialisation: e.g. strict tree structures.

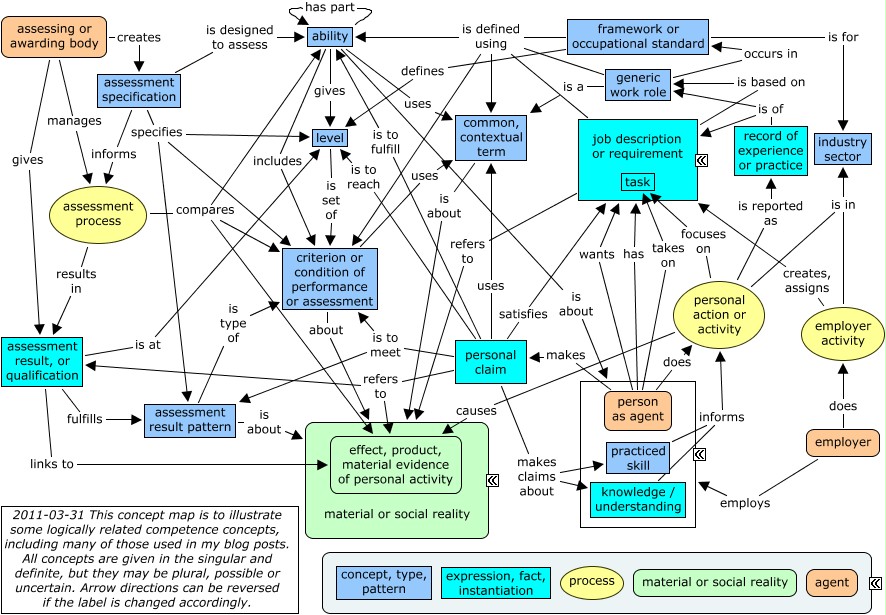

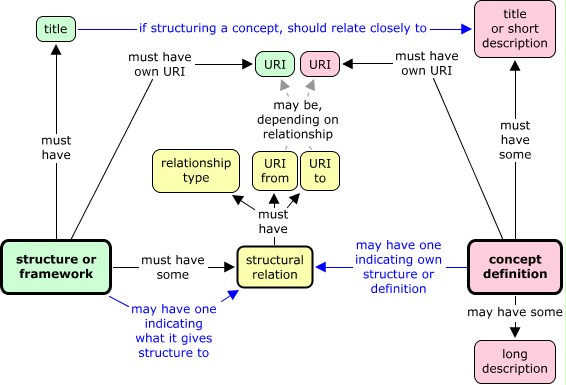

In the case of the logic of competence, as I discussed in post 12 in the series, we want to represent both individual competence concepts (or abilities) and structures or frameworks that include several of them.

Published competence frameworks generally use plain text as a medium — they are not primarily graphical or diagrammatic — and have therefore in a sense already been serialised by the publishers. They come across overall rather like a tree structure, though there are very often cross-references and/or repetitions that betray the fact that the information is in reality more complex than a simple tree. But the structure is close enough to a tree to tempt people to want to represent it as such. This is nicely illustrated in Alan Paull’s comment on post 12. Alan’s ability definitions are nested within each other: a depth-first traversal serialisation of the tree if you like.

As Alan and I have agreed in conversation, it is possible to convert a tree-like competence structure to and from other forms. I’ll now give three other forms, and explain how the conversion can be done, and following that I’ll discuss the implications. I’ll call the forms: Atom-like; disjoint; and triples.

First, it can be transformed to a format similar to Atom, where each separate thing (for Atom: entry; here: ability) is given in a flat list of things, each thing including the links between it and other things. (Atom is the format we adopted for Leap2A.) To do this, you take each ability from the tree structure and put it into a flat list, replacing the relation to the nested ability with one using only its identifier, and adding a reverse link from the narrower ability to the broader ability it was removed from. It is also possible to reverse this procedure — start by finding the broadest ability definition (that is, the one which is has no broader links) and then replace narrower links by the whole narrower ability definition, removing the narrower ability’s link to the broader ability. If a narrower ability has already been put in place, leave the reference in place, to avoid duplication.

Second, it can be transformed into a disjoint structure with all the relationships separated out. It’s perhaps easiest to imagine this starting from the Atom-like format, as in the Atom-like format each ability has already been separated out, and there are fewer steps to reach the disjoint form. For each link within each ability, convert it to a separate relationship whose subject is the ability where it is defined, and whose object is the ability referenced. Separate the relationships, leaving the ability definitions with no relationship information included within their structure. An extra step of de-duplication can then occur, because probably the Atom-like format had two representations of each relationship: A narrower B and also the equivalent B broader A. Only one of each pair like this is needed to represent the structure fully.

As in the previous case, it is straightforward to reverse this transformation. For each ability, find the relationships which involve that ability identifier. If the relationship has the ability identifier in the subject position, include a link to the object ability within the ability. If the ability identifier is in the object position, include a link with the reciprocal relationship to the other ability.

Third, it can be transformed by being broken right down into RDF triples. As before, it is easiest to start with the nearest other form — in this case the disjoint one. Take each disjoint ability definition (without relationships). This should convert to a set of triples each with the ability identifier as subject, and probably a literal object. The separate relationships are already in a triple-like format, so they can be converted very easily. To reverse this transformation, examine each triple in turn. If subject and object are ability identifiers, turn the triple into a relationship. Then, for each ability, find all triples that have the identifier of that ability as the subject, and have a literal object, and build a single ability structure out of that set.

Now we’ve seen that these different formats are interconvertable, so which one you use does not impede the communication of a complete ability or competence framework. Where they do differ, however, is in what identifiers are seen to identify, and that does have implications, at least for human use.

Identifiers in RDF triples don’t really identify anything by themselves. An RDF resource is simply a node, with a URI as an identifier. RDF relationships have been called predicates or properties, which is nicely ambivalent about how tight the relationship is. RDF doesn’t tell you which relations relate to things that should be considered as part of the essence of the identified “resource” — or what is inside the “skin” of the resource, if you like. The only thing you can say, when grouping RDF triples together, is that literal properties don’t make any sense by themselves, so they can be seen as attached to, or hang off, a “resource”. In the discussion above, we have assumed that the abilities are the only kind of resources we are dealing with, and that will guide the conversion from the “triples” form to the “disjoint” form.

In the disjoint form, literal properties are grouped with the abilities they are properties of. These properties are likely to include the very well-known ones of title and description at least. The fact that relations are listed separately implies that the relationships are less essential to the nature of an ability than its title and description. In the Atom-like form, an identifier looks like it refers to an ability together with all of its immediate relationships. But in the tree-like form, the identifier of a broader ability seems to refer to the complete structure branching down from it.

Which of these is the most useful or flexible way to identify abilities? That is a real question, and I believe it was the question implicitly underlying much of the discussion at the meeting I participated in earlier this week.

One way of tackling the issue of what is the most useful way of doing identifiers is to look at when you would want to change the identifier. There’s not much one can say about this for RDF triples. For the disjoint form, an identifier would want to change typically when the title or description changes. For Atom-like form, the identifier might reasonably change if any of the direct relationships changed. For broader tree-like structures, the implication is that the identifier should change if any of the structure changes.

When an ability identifier changes is significant. Effective connection between what is taught, learned, assessed, required, claimed or evidenced is only assured if the same identifier is used. If different ones are used for essentially the same ability, extra provision needs to be made to ensure, e.g., that evidence for the ability under one ID can be used to fulfill requirements under a different ID. That provision might be in terms of declaring that two ability IDs actually are equivalent. So, generally speaking, it is reasonable to have ability identifiers changing only when necessary — when what the ability means in practice has actually changed.

So now we can ask: which approach to structuring ability or competence definitions delivers this outcome of needing changed identifiers no more (and no less) than necessary?

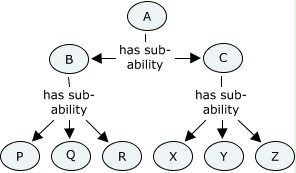

The first sub-question I’d like to address is: should changing structure always require changing identifier? My answer is clearly, no, not always, and this is the reasoning. Yes, of course you should change the identifier if the content has changed. But structure change does not strictly imply content change. After thinking a long time about this, I think the clearest example is with intermediate layers of structure. And, happily, this is illustrated in real life with several UK National Occupational Standards. OK, so imagine we have a three-layer competence / ability structure.

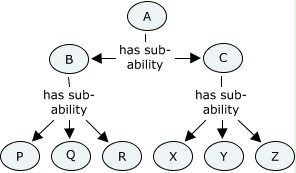

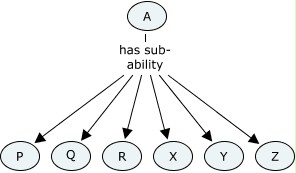

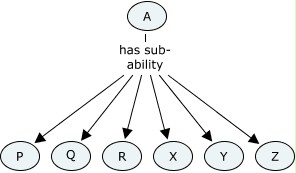

Top ability A has two sub-abilities, B and C. B is further divided into P, Q and R, while C is further divided into X, Y and Z. (In real life, there would usually be more.)

The body that defines the structure decides that the justification for the intermediate layer is rather flimsy, and removes it, leaving the structure that ability A has direct sub-abilities P, Q, R, X, Y and Z. The title and long definition of A are unchanged. Is A the same ability? I would answer, unequivocally, yes it is, because all evidence the former A is also equally evidence for the latter A.

Or apply this to the BSHAPM pizza making ability example. A stands for the ability to make pizza the BSHAPM way. B could be baking pizza. P, Q and R could be the three approaches to pizza baking. The BSHAPM could decide that, for simplicity, they wanted to eliminate the node of baking pizza as a separate ability, and instead represent the three approaches to baking pizza as direct sub-abilities of pizza making.

Now if you cling to the view that changes in structure must result in changes of identifier, this means that you will need to declare, and process, a whole extra kind of relationship: that the former A is equivalent to the latter A. This strikes me as unnecessary and quite possibly confusing. Possible: yes; ideal: no. The same example also goes against the Atom-style idea of ability identity. The immediate relationships of ability A change in this scenario, without the ability itself changing at all.

Thus, if we still want to deliver the outcome of changing the identifier only as much as necessary, not more, we are driven to the next type of structural representation, the “disjoint” one. But this comes with a caution. If we are not including the structure as an essential part of the ability or competence definition, we need to be sure that we aren’t cutting corners, and omitting to give a full description of the ability that we can use as a proper definition. Sometimes this may happen in cases where the structure is defined at the same time as the contained abilities. We may simply say that ability A is defined as the sum of abilities B, C and D. Then we risk not noticing that the substance, the content, of an ability has changed, when we change it to being composed of B, C, D and E. So, there is a requirement, to use this “disjoint” approach, that we properly define the ability, in such a way that if an extra component is added, we feel we need to change the definition, and thus the identifier with it. I would say that amounts to no more than good practice. At very least, we should have a long description that states that ability A consists of B, C and D (or B, C, D and E). Or we may choose to make explicit, in text that is not formally structured, the fact that ability A is actually made up of the things that are grouped together under the headings, B, C, etc. Usually, ability A will actually have more to it than simply the sum of the parts. One would expect at least that ability A would include the ability to recognise when abilities B, C, etc. are appropriate, and apply them accordingly, or something like that. So, again, failing to write a full definition or long description is laziness and bad practice.

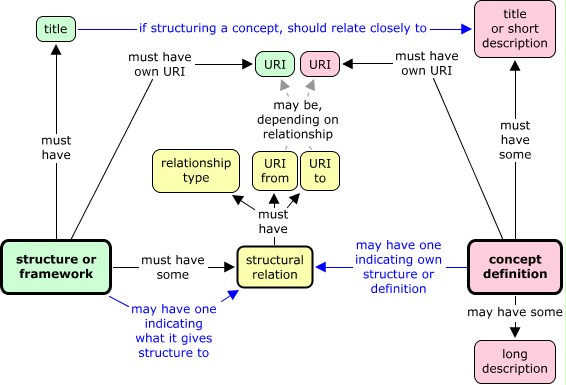

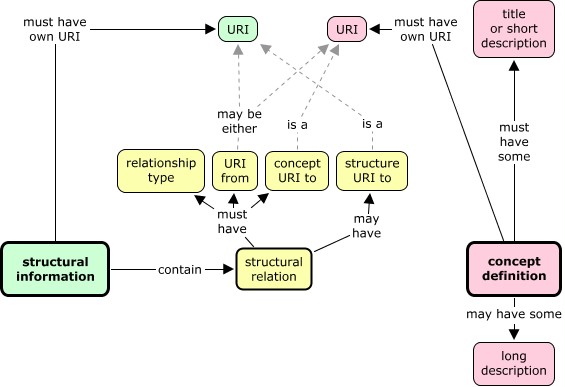

This reflects back on what I said earlier about a structure doubling as a concept in its own right, or in other words a framework doubling as an ability definition (which also I have actually changed now so as not to have too much hanging around that I no longer believe). Perhaps that needs qualifying and clarifying now. The way I would put it now is that in authoring a competence structure, I am usually implicitly defining a competence concept, but good practice demands that I define that concept explicitly in its own right. It is then true to say that the structure “gives structure to” the concept, in the sense that it details a certain set of narrower parts that the broader concept “contains”. But that is certainly not the only way of structuring the concept. My example based on real NOS cases is only the tip of the iceberg — it is very easy indeed to make up endless examples where the same broad ability is structured in different ways.

It is also not true that a structure necessarily defines a clear single concept. In many cases (such as my BSHAPM pizza making ability) it may, but in very broad cases it may not do. We cannot have that as a requirement for a representation. Thus, contrary to what I wrote at one point previously, it is plausible to have a structure or framework title and definition that is independent of an ability title or definition. It’s just that you can’t use one as the other, and it’s more usual, in less broad cases, to have the structure and the ability concept closely related, perhaps even sharing the title. The structure should not, however, have a long description anything like an ability concept.

Thus, the structure “gives structure to” the concept, and the concept “is structured by” the structure.

Perhaps it is worth remembering that a major envisaged use of these structures, in their structured electronic (rather than less explicitly formatted document) form, is to give learners a set of discrete concepts to which evidence can apply, which can be self-assessed or assessed by others, which can be claimed, or required. Some kind of “container” element at least is necessary in which an ability can be contained or not. The container seems to be exactly the explicit framework structure. In the three-layer example above, the definition, identifier and title of ability A can remain the same, while the framework structure can change from containing in the first case A, B, C, P, Q, R, X, Y and Z and in the latter case A, P, Q, R, X, Y and Z. Applied to pizza making, the frameworks would have to be given better titles than “structure for baking pizzas (layers)” and “structure for baking pizzas (flat)”!

I’d like to conclude by pointing out the trade-off involved in taking the different paths.

- if you proliferate identifiers due to changing identifiers each time the structure changes, you’ll need extra mechanisms to pin together different “versions” of ability definitions that differ only in their structure, or the extent of their structure, not in their substance or content;

- if you want to keep the same ability identifier when the structure changes but not the content, you’ll need to take care to make long descriptions explicit; and to separate identifiers for structure and ability, pinning them closely together where appropriate.

With the latter option, I’m claiming that the ability identifier will naturally change in just those cases where one would want it to change. The cost is getting one’s head round the difference between the ability and the structure. I firmly believe it is worth the effort for system designers to do this, so that the software can handle things properly behind the scenes, while not needing to trouble the end users with thinking about these matters. I’m also suggesting that the latter option requirements embody good practice, where the former ones do not.

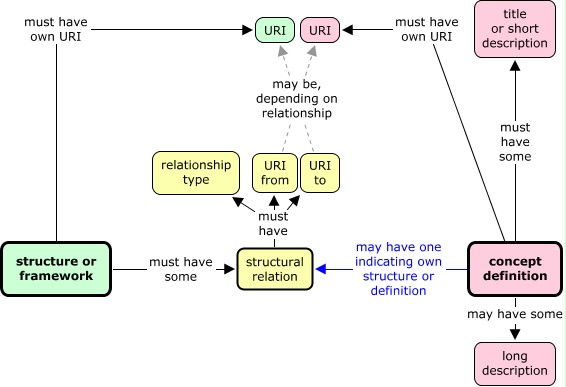

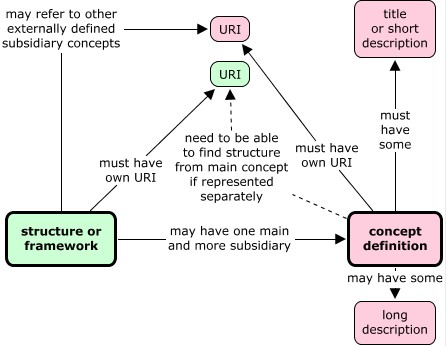

This gives us one step forward on the structure diagram from the last two posts, 12 and 13.

Next I’ll firm up on why allowing optionality in competences structures is a good idea, before going on to saying more about how to represent level attributions and level definitions.