Last week, seven OER projects from the institution strand of UKOER pilot programme gathered together at Nottingham University to share the outcomes of the projects and common issues they are trying to address which I found very useful and stimulating. The meeting started with OER showcases in which each project presented two resources they have made available through their project. Some of the examples are available on the project websites and JorumOpen. Here is the list of the projects and the features of the resources that were presented:

- BERLiN (University of Nottingham) – a 6 credits PGCE international course and resources created in the Second Life;

- Unicycle (Leeds Metropolitan University) – virtual maths, a 6 credits course;

- Open Exeter (University of Exeter) – a complete modular for self-paced learning;

- OpenStaffs (Staffordshire University) – Individual images for reuse and repurposing;

- OTTER (University of Leicester) – a framework for transforming teaching materials into OERS;

- OpenSpires (University of Oxford) – Oxford seminars and public lectures-based resources;

- OCEP (Coventry University) – diverse content types, such as Second Life machinima, looking into how one set of resources could be used in different ways.

The meeting also provided an opportunity for projects to share experiences and discuss issues on reward and recognition for producing OERs, developing sustainable OER models, resources discovery and copyright clearance, etc. There were several themes raised during the presentations and discussions:

- Quality control: how should institutions control the quality of OERs provided by lecturers? On the one hand, quality is very critical from the marketing perspective since these resources are showcases of universities’ courses. On the other hand, if the goal of OERs is to promote sharing, reusing and repurposing, then the quality of the resources should be judged by the end users rather than institutions.

- Centralised and distributed models: it has been reported that some projects have adopted a centralised model which means that staff have been employed by the project to provide technical and other supports for procuring and releasing OERs. However, there are concerns about whether universities would continue fund this support when the project finished. One of the projects adopted a distributed model for which no additional staff has been recruited and the responsibilities for producing OERs have been located to representatives from different faculties. It is hoped that these people would continue to do so after the OER programme ends.

- Shrinking credits: there have been concerns about producing 360 credits equivalent teaching and learning resources at the end of the programme. Some projects found they are struggling to meet this requirement. One of the reasons mentioned was “shrinking credits”. For example, a lecturer may promise to provide 30 credits course materials, however, when the course materials turn to OERs, it might turn out to be much less than 30 credits. This is understandable, when we talk about credits which involve content, teaching and learning process and assessment. In this sense, if it is content alone, credits may be not the most appropriate way to measure the OER projects. However, it is agreed that the UK OER programme does expect to make significant amounts of teaching and learning resources freely available.

According to The New Media Consortium the Horizon Report 2010, open content is expected to reach mainstream teaching and learning within one year or less. In this case, what these institution projects have learned from the UK OER pilot programme would be really valuable to this movement.

Two weeks ago, I joined my colleagues, Oleg Liber, Director of JISC CETIS and Sarah Holyfield, Communications Director of JISC CETIS to present at

Two weeks ago, I joined my colleagues, Oleg Liber, Director of JISC CETIS and Sarah Holyfield, Communications Director of JISC CETIS to present at

was organised by the Higher Education Press in Beijing on 24th August. The speakers from different Chinese universities reported findings from their projects and research on use of technology to enhance teaching and learning. I was invited to give a presentation on

was organised by the Higher Education Press in Beijing on 24th August. The speakers from different Chinese universities reported findings from their projects and research on use of technology to enhance teaching and learning. I was invited to give a presentation on

Finally and most interestingly, we found a street storyteller using an old fashion technology –“Magic Lantern” to present Chinese history stories which attracted many people (different age, gender and culture) who came to visit the modern Shanghai.

Finally and most interestingly, we found a street storyteller using an old fashion technology –“Magic Lantern” to present Chinese history stories which attracted many people (different age, gender and culture) who came to visit the modern Shanghai.

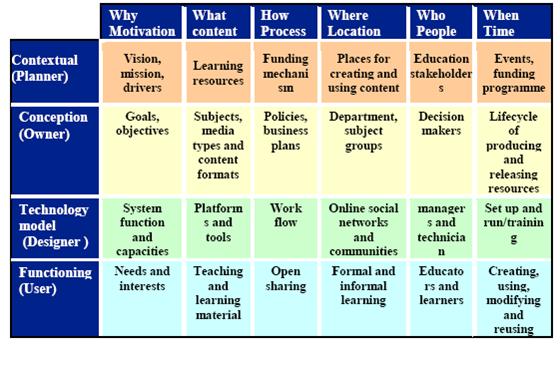

In the table, the four rows present different points of view from various players related to OERs, namely: the planner, owner, designer and user. The information provided in each cell could become knowledge to help us share and understand different perspectives from different players in the process. For example, the motivation factor, requires the planner, owner, designer and user to come up with answers to the “why” question, i.e. why is there a need for OER? Why are the various choices made? It concerns the translation of goals and strategies into specific ends and means.

In the table, the four rows present different points of view from various players related to OERs, namely: the planner, owner, designer and user. The information provided in each cell could become knowledge to help us share and understand different perspectives from different players in the process. For example, the motivation factor, requires the planner, owner, designer and user to come up with answers to the “why” question, i.e. why is there a need for OER? Why are the various choices made? It concerns the translation of goals and strategies into specific ends and means.