Last week, David Kernohan and myself attended three conferences in North America, all with a common underlying theme of open. But, as many of us know, there are many types/flavours/definitions of open in education today. This post tries to make sense of some of the common themes across the week.

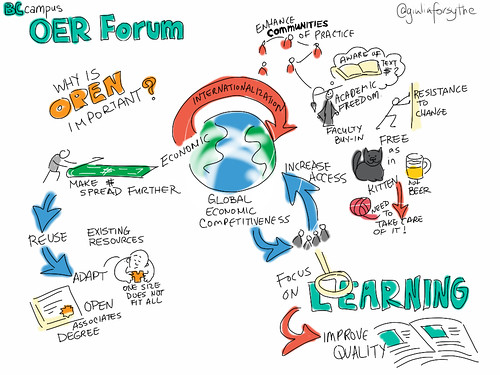

The Ithaka Sustainable Scholarly Research Conference and OpenEd 2012 were in some ways at opposite sides of the open spectrum. The former being research and (research) publisher orientated, with Open Access featuring prominently, and OpenEd being very much focused on the use and development of open content and open educational practice. We also attended a half day Open Forum hosted by BCcampus which was designed to initiate discussions and action around developing a province wide approach to open education in general which again had a different flavour (visually noted by Guilia Forsythe )

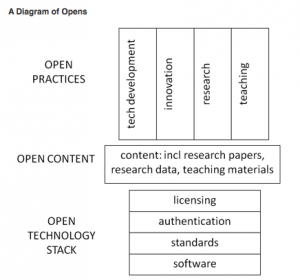

As I’ve been trying to focus and write up coherent account of the week, a couple of posts have come to mind. Firstly, Amber Thomas’s diagram of openness;

A Diagram of Opens, Amber Thomas, 2012

http://infteam.jiscinvolve.org/wp/2012/01/17/storyo/

which is really useful it setting out the areas covered last week, with an emphasis on the open content and open practices areas.

There were lots of cross over points, which is how it should be. As Amber points out in her original post “There is not ever going to be a total transformation to open. The reality is a mixed economy.” And I was really heartened to see how a number of presentations at OpenEd are embracing this point of view. I’ve always had a niggling concern that the OER movement might be guilty of a form of self ghettoisation, by just talking to itself about what it is doing and not embracing the wider community. In particular the presentation by Emily Puckett Rodgers and Dave Malicke from Open Michigan outlined the more inclusive approach they have developed in engaging practitioners with open practice, sharing and OERs was a great example of wider community engagement.

Open Michigan trying to understand culture of sharing in institution – not to being too dogmatic about “purity” of open content #opened12

— Sheila MacNeill (@sheilmcn) October 18, 2012

Their approach is now far more about understanding motivations for sharing and then working with staff and students to build confidence, understanding and sharing of content in appropriately open ways rather than trying to ensure content is in the “right” format.

Open Access was also a linking theme. The Ithaka conference was situated squarely within the research and publishing sphere. I am very much on the periphery of this area (please read the rest of this section with that in mind), but it was quite fascinating to sit in on some of the discussions, particularly those around new models of publishing and peer review. As this is Open Access Week, I found it timely to read far more informed comment on the OA debate from both Peter Murray Rest and Martin Weller yesterday.

I rather naively anticipated general support and consensus about OA. During the conference I got an insight into another side of the debate. A round table session featuring a university press, and two subject associations highlighted their pressures around OA. Whilst recognising the need to evolve and change, it was pointed out many smaller associations and publishers exist for their publication, not to make profit. Many of them don’t receive any other funding so rely on their sales just to survive. But there was general recognition that a journal alone was no longer a sustainable model. There needs to be more exploration of new models including moving from print to wholly online publishing, looking at extending value through increased and improved access to scholarly databases and/or bibliographies, exploring the potential of producing more case studies with teaching notes and industry reports and surveys. Journals need to change from just being text based to including other types of content (video, data etc).

The need for hybrid OA approaches with more community/crowdsourced approaches to peer review was also a common theme. This was followed up in in a session called “Next Generation Peer Review”, where a number of OA platforms such as PLOS One, F1000 Research, Rubriq and a new addition to the market PeerJ were highlighted. PeerJ is launching next month, and is being designed to take have a very community driven approach. Initial membership is $99 per year, and they are hoping to reduce that to zero by selling other data. Exactly what/how that would work is as yet unclear. But that certainly seemed to chime with what the smaller publishers were saying the day before. This approach also seemed to be drawing on ideals of scholarly societies where membership and reviews are trusted and more importantly open processes.

Obviously there needs to be more experimentation around open review processes which was discussed but there are certainly opportunities to expand OA approaches and perhaps open peer review could be a disruptive force in this area. I’ve pulled my twitter notes from these sessions together in a storify as they capture the essence of the discussions.

The need for more open access, particularly for publicly funded research was the starting point for John Willinsky’s keynote at OpenEd, where he made a rallying cry for the extended right to and power of open access, open data and open education. Again more merging and mixing of the elements of Amber’s diagram.

One other thing that really stuck out for me (and a couple of other delegates) at OpenEd was the omnipresence of the e-book. Whilst I fully appreciate that bringing down the cost of text books, and of course making as many texts as possible available under open licences such as CC, is a great thing (not least for the amount of money it can save students and institutions); it did seem that e-books were the only concern of some presentations. I did feel slightly uneasy about the tyranny of text book particularly as theme of the conference was “beyond content”. But, given the cost of some text books and the fact that you don’t seem to be able to pass any college courses in North America without access to set texts I can see why many sessions were centered around this. Maybe it’s just a British thing, and I should feel fortunate that, as yet, we don’t have similar pressures. I think (hope!) the presentation David and I did on the history of OER from a UK perspective highlighted a non-content centric view of development.

The BC Openforum also had a strong element of the absurdity of some book costs – particularly in the K-12 sector. Both David Wiley and Cable Green (Creative Commons) highlighted how taking open approaches to the creation and extension of text books can save money and so allow for more time and money to be spent on staff development and in turn more creative approaches to teaching and learning. Moving to more open practices, Brian Lamb also shared a number open approaches, including DS106 – couldn’t do a post on OpenEd without mentioning it somewhere ![]() It was good to hear an embracing of the “proudly borrowed from here” spirit advocated by Cable in the delegate discussion sessions. In the spirit of openness, collated notes from the discussion sessions are available online.

It was good to hear an embracing of the “proudly borrowed from here” spirit advocated by Cable in the delegate discussion sessions. In the spirit of openness, collated notes from the discussion sessions are available online.

So all in all a mixed mode week of open-ness, but it was great to see more and more interconnectedness of the jigsaw of open education.