eBooks is one of technologies that many believe will have significant impact on education; and indeed will change the way of teaching and learning in schools and universities. In essence, both eBooks and printed books are very similar in as much as they allow people to do the most important thing – read a book. However, compared to traditional books, eBooks offer new ways to distribute and interact with information. Take, for example, the eBook produced by the Oxford Internet Institute, “Geographies of the World’s Knowledge”, a research report on where and how knowledge is distributed across the world. Readers can select pieces of the pictures in this book to zoom in on and to glean further information as they wish. They can navigate to particular pages via interaction with the visualizations.

The rapid development of E-readers, tablets and mobile technology in recent years, such as Kindles, iPads and smartphones makes buying, downloading and reading eBooks more popular and easier. As a result, more and people are reading routinely on their electronic devices. In particular, the younger generation, reading is the tool for much social activity and experience through the sharing of notes and comments instantly. With these social networking developments, it is clear that there will be increased demand from learners for eBooks within academic contexts. Education will need to change to provide a more interactive learning experience and access to content anytime, anywhere as promised by using eBooks.

However, despite all the hype, eBooks have remained on the fringes of higher education. For institutions, eBook technology is still new. There are many questions needing to be answered in order to embed eBooks in teaching, learning and research. For example, is eBook technology mature enough for education? Is it time to invest heavily in e-textbooks in institutions? What are the technical and cultural challenges we are facing and how can eBooks be best used in academic contexts? We don’t know the answers to all of the questions, but it is clear that we need more information and knowledge about eBooks to make well informed decisions.

Hopefully, the newly published JISC Observatory TechWatch report on “Preparing for Effective Adoption and Use of Ebooks in Education” will help decision makers, IT managers, librarians and educators to gain a better understanding of current issues and challenges in adopting eBooks in institutions. In this report, the author, James Clay, introduces the history and key concepts of eBooks and discusses the technical, cultural and legal challenges that need to be addressed for the successful adoption of eBooks in education. Furthermore, it offers scenarios illustrating the effective use of eBooks in libraries and in teaching, learning and research in institutions. It also provides us with useful insights into the future directions of eBook development.

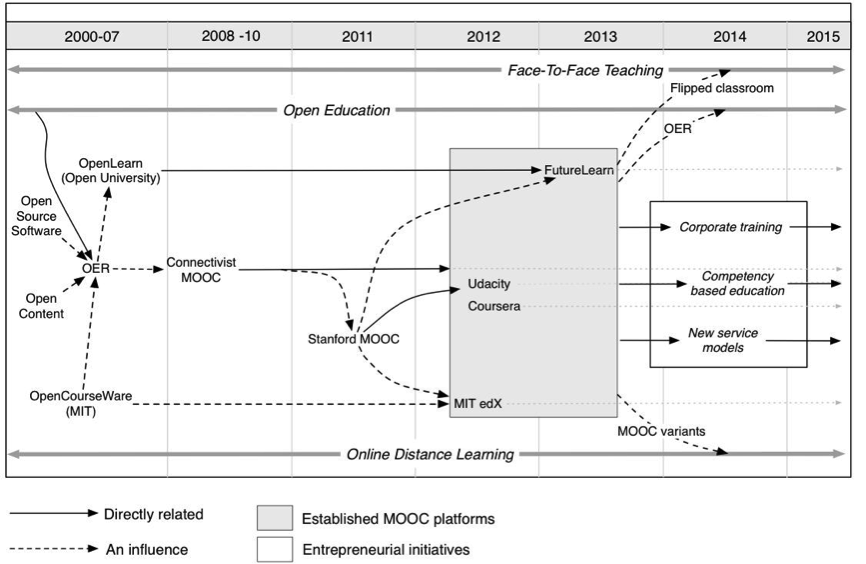

This revised version of the evolution of MOOCs was developed for our paper ‘Partnership Model for Entrepreneurial Innovation in Open Online’ now published in eLearning Papers.

Three years after the initial MOOC hype, in line with our previous analysis we looked at some possible trends and influence of MOOCs the HE system in the contexts of face-to-face teaching, open education, online distance learning, and possible business initiatives in education and training. We expanded the diagram from 2012 -2015 and explored some key ideas and trends around the following aspects:

This revised version of the evolution of MOOCs was developed for our paper ‘Partnership Model for Entrepreneurial Innovation in Open Online’ now published in eLearning Papers.

Three years after the initial MOOC hype, in line with our previous analysis we looked at some possible trends and influence of MOOCs the HE system in the contexts of face-to-face teaching, open education, online distance learning, and possible business initiatives in education and training. We expanded the diagram from 2012 -2015 and explored some key ideas and trends around the following aspects: