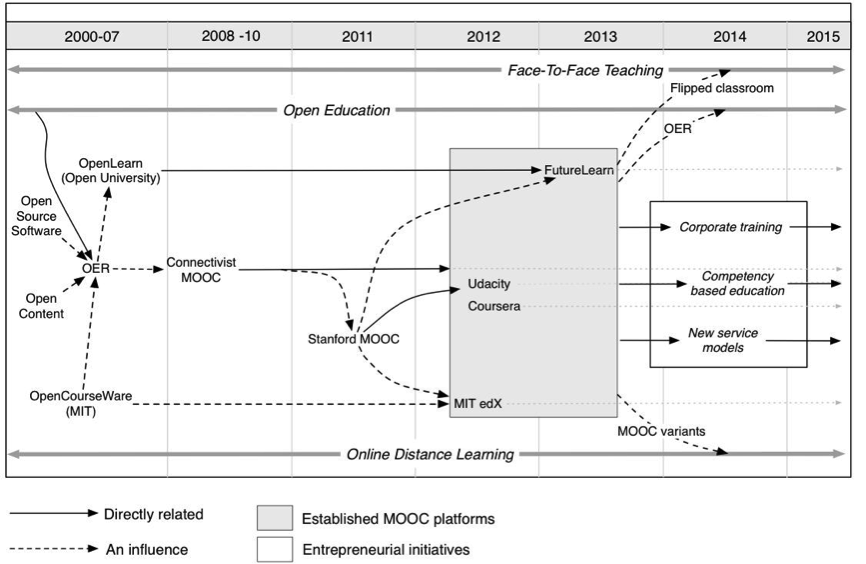

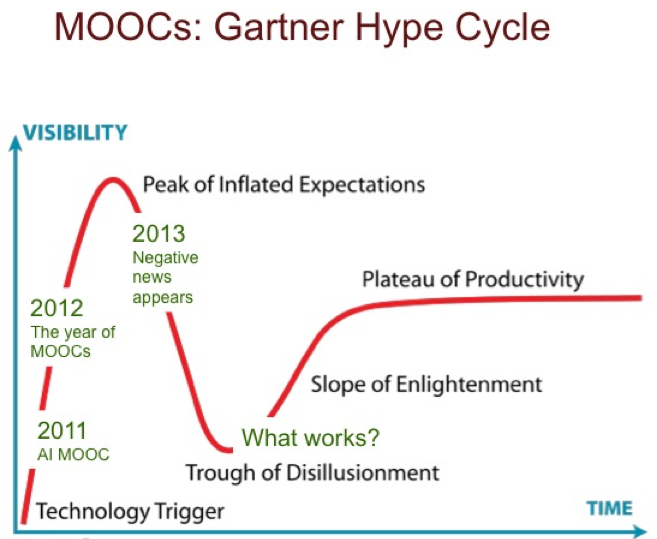

This revised version of the evolution of MOOCs was developed for our paper ‘Partnership Model for Entrepreneurial Innovation in Open Online’ now published in eLearning Papers.

Three years after the initial MOOC hype, in line with our previous analysis we looked at some possible trends and influence of MOOCs the HE system in the contexts of face-to-face teaching, open education, online distance learning, and possible business initiatives in education and training. We expanded the diagram from 2012 -2015 and explored some key ideas and trends around the following aspects:

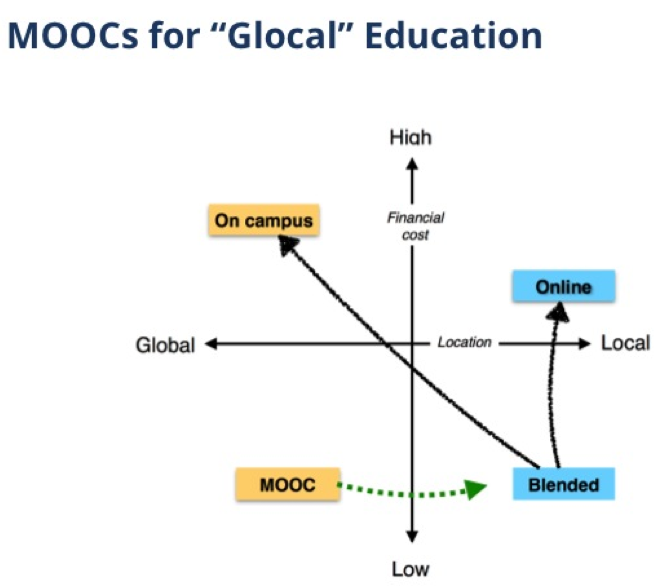

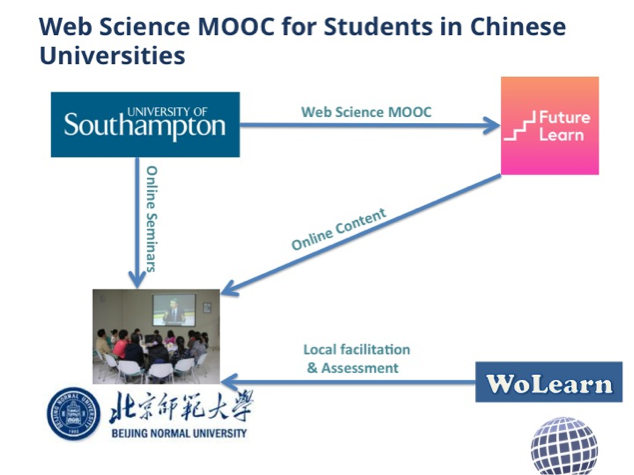

- Open license: Most MOOC content is not openly licensed so it cannot be reused in different contexts. There are, however, a few examples of institutions using Creative Commons licences for their courses – meaning they can be taken and re-used elsewhere. In addition, there is a trend for MOOC to be made available ‘on demand’ after the course has finished, where they in effect become another source of online content that is openly available. Those OERs and online content can be used to develop blended learning courses or support a flipped classroom approach in face-to-face teaching.

- Online learning pedagogy: New pedagogical experiments in online distance learning can be identified in addition to the c/xMOOC with variants including SPOCs (Small Private Open Courses), DOCCs (Distributed Open Collaborative Course) and SOOCs (Social Online Open Course or Small Open Online Course). It is likely that they will evolve to more closely resemble regular online courses with flexible learning pathways. These will provide a range of paid-for services, including learning support on demand, qualitative feedback on assignments, and certification and credits (Yuan and Powell 2014).

- New educational provisions: The disruptive effect of MOOCs will be felt most significantly in the development of new forms of provision that go beyond the traditional HE market. For example, the commercial MOOC providers, such as Udacity and Coursera, have moved on to professional and corporate training, broadening their offerings to appeal to employers (Chafkin, 2013). In an HE context, platforms are creating space for exam-based credit and competency-based programs which will enable commercial online learning providers to produce a variety of convenient, customizable, and targeted programs for the emergent needs of the job market backed by awards from recognised institutions.

- Add-on Services: The development of online courses is an evolving model with the market re-working itself to offer a broader range of solutions to deliver services at a range of price levels to a range of student types. There is great potential for add-on content services and the creation of new revenue models through building partnerships with institutions and other educational service providers. As these trends continue to unfold, we can expect to see even more entrepreneurial innovation and change in the online learning landscape.