Cetis (the Centre for Educational Technology, Interoperability and Standards) and the IEC (Institute for Educational Cybernetics) are full of rich knowledge and experience in several overlapping topics. While the IEC has much expertise in learning technologies, it is Cetis in particular where there is a body of knowledge and experience of many kinds of standardization organisations and processes, as well as approaches to interoperability that are not necessarily based on formal standardization. We have an impressive international profile in the field of learning technology standards.

But how can we share and pass on that expertise? This question has arisen from time to time during the 12 years I’ve been associated with Cetis, including the last six working from our base in the IEC in Bolton. While Jisc were employing us to run Special Interest Groups, meetings, and conferences, and to support their project work, that at least gave us some scope for sharing. The SIGs are sadly long gone, but what about other ways of sharing? What about running some kind of courses? To run courses, we have to address the question of what people might want to learn in our areas of expertise. On a related question, how can we assemble a structured summary even of what have we ourselves have learned about this rich and challenging area?

These are my own views about what I sense I have learned and could pass on; but also about the topics where I would think it worthwhile to know more. All of these views are in the context of open standards in learning technology and related areas.

How are standards developed?

A formal answer for formal standards is straightforward enough. But this is only part of the picture. Standards can start life in many ways, from the work of one individual inventing a good way of doing something, through to a large corporation wanting to impose its practice on the rest of the world. It is perhaps more significant to ask …

How do people come up with good and useful standards?

The more one is involved in standardization, the richer and more subtle one’s answer to this becomes. There isn’t one “most effective” process, nor one formula for developing a good standard. But in Cetis, we have developed a keen sense of what is more likely to result in something that is useful. It includes the close involvement of the people who are going to implement the standard – perhaps software developers. Often it is a good idea to develop the specification for a standard hand in hand with its implementation. But there are many other subtleties which could be brought out here. This also begs a question …

What makes a good and useful standard?

What one comes to recognise with time and experience is that the most effective standards are relatively simple and focused. The more complex a standard is, the less flexible it tends to be. It might be well suited to the precise conditions under which it was developed, but those conditions often change.

There is much research to do on this question, and people in Cetis would provide an excellent knowledge base for this, in the learning technology domain.

What characteristics of people are useful for developing good standards?

Most likely anyone who has been involved in standardization processes will be aware of some people whose contribution is really helpful, and others who seem not to help so much. Standardization works effectively as a consensus process, not as a kind of battle for dominance. So the personal characteristics of people who are effective at standardization is similar to those who are good at consensus processes more widely. Obviously, the group of people involved must have a good technical knowledge of their domain, but deep technical knowledge is not always allied to an attitude that is consistent with consensus process.

Can we train, or otherwise develop, these useful characteristics?

One question that really interests me is, to what extent can consensus-friendly attitudes be trained or developed in people? It would be regrettable if part of the answer to good standardization process were simply to exclude unhelpful people. But if this is not to happen, those people would need to be to be open to changing their attitudes, and we would have to find ways of helping them develop. We might best see this as a kind of “enculturation”, and use sociological knowledge to help understand how it can be done.

After answering that question, we would move on to the more challenging “how can these characteristics be developed?”

How can standardization be most effectively managed?

We don’t have all the answers here. But we do have much experience of the different organisations and processes that have brought out interoperability standards and specifications. Some formal standardization bodies adopt processes that are not open, and we find this quite unhelpful to the management of standardization in our area. Bodies vary in how much they insist that implementation goes hand in hand with specification development.

The people who can give most to a standardization process are often highly valued and short of time. Conversely, those who hinder it most, including the most opinionated, often seem to have plenty of time to spare. To manage the standardization process effectively, this variety of people needs to be allowed for. Ideally, this would involve the training in consensus working, as imagined above, but until then, sensitive handling of those people needs considerable skill. A supplementary question would be, how does one train people to handle others well?

If people are competent at consensus working, the governance of standardization is less important. Before then, the exact mechanisms for decision making and influence, formal and informal, are significant. This means that the governance of standards organisations is on the agenda for what there is to learn. There is still much to learn here, through suitable research, about how different governance structures affect the standardization process and its outcomes.

Once developed, how are standards best managed?

Many of us have seen the development of a specification or standard, only for it never really to take hold. Other standards are overtaken by events, and lose ground. This is not always a bad thing, of course – it is quite proper for one standard to be displaced by a better one. But sometimes people are not aware of a useful standard at the right time. So, standards not only need keeping up to date, but they may also need to be continually promoted.

As well as promotion, there is the more straightforward maintenance and development. Web sites with information about the standard need maintaining, and there is often the possibility of small enhancements to a standard, such as reframing it in terms of a new technology – for instance, a newly popular language.

And talking of languages, there is also dissemination through translation. That’s one thing that working in a European context keeps high in one’s mind.

I’ve written before about management of learning technology standardization in Europe and about developments in TC353, the committee responsible for ICT in learning, education and training.

And how could a relevant qualification and course be developed?

There are several other questions whose answers would be relevant to motivating or setting up a course. Maybe some of my colleagues or readers have answers. If so, please comment!

- As a motivation for development, how can we measure the economic value of standards, to companies and to the wider economy? There must be existing research on this question, but I am not familiar with it.

- What might be the market for such courses? Which individuals would be motivated enough to devote their time, and what organisations (including governmental) would have an incentive to finance such courses?

- Where might such courses fit? Perhaps as part of a technology MSc/MBA in a leading HE institution or business school?

- How would we develop a curriculum, including practical experience?

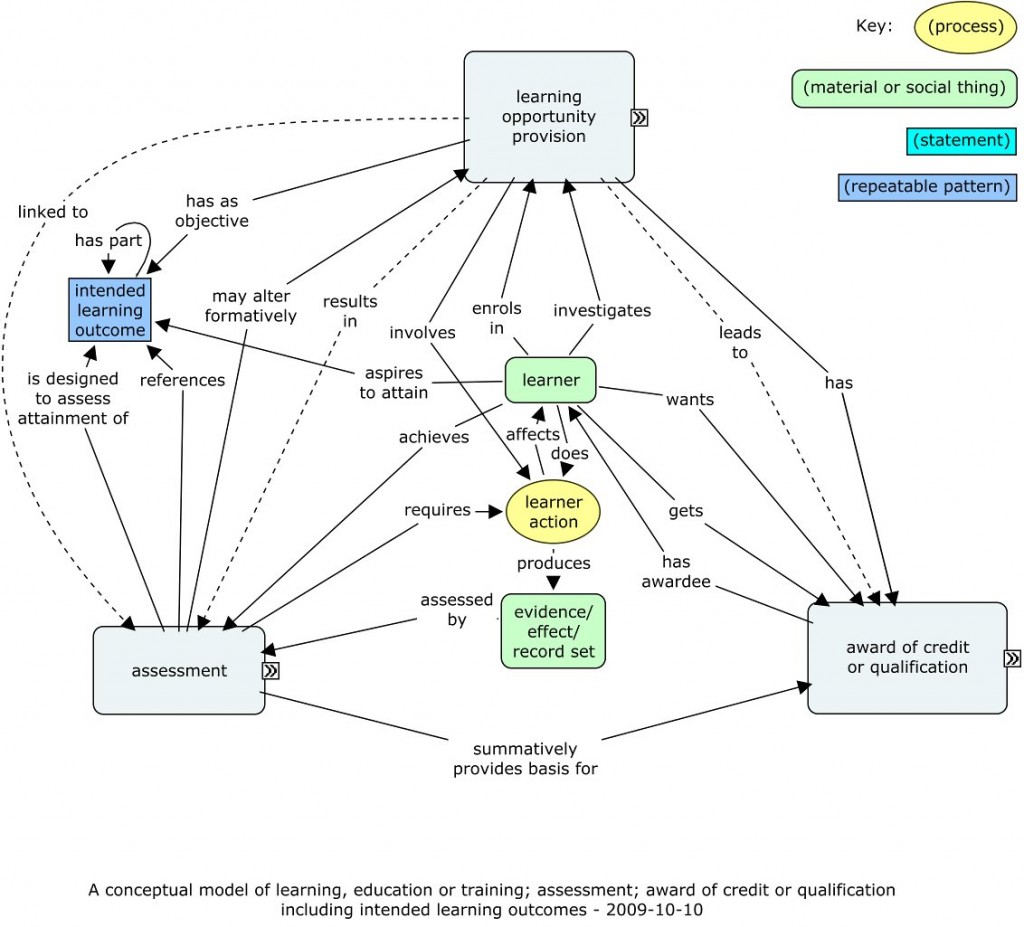

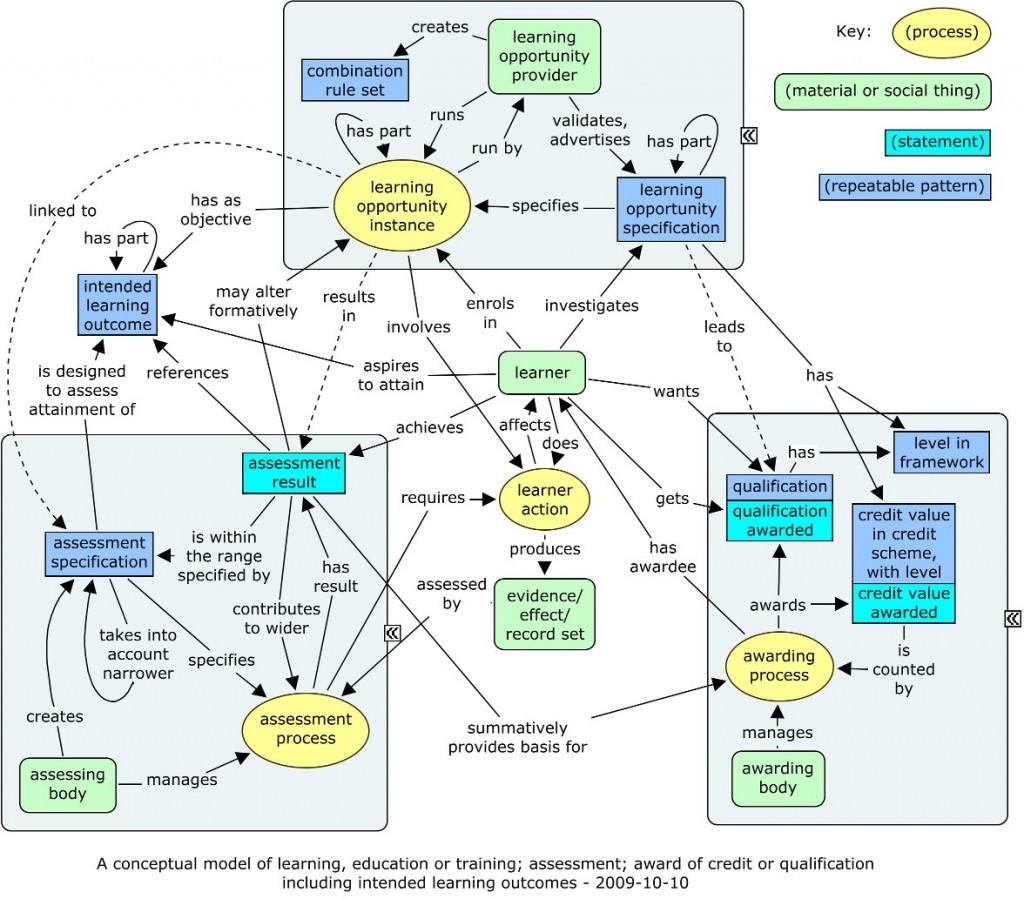

- How could we write good intended learning outcomes?

- How would teaching and learning be arranged?

- Who would be our target learners?

- How would the course outcomes be assessed?

- Would people with such a qualification be of value to standards developing organisations, or elsewhere?

I would welcome approaches to collaboration in developing any learning opportunity in this space.

And more widely

Looking again at these questions, I wonder whether there is something more general to grasp. Try reading over, substituting, for “standard”, other terms such as “agreement”, “law”, “norm” (which already has a dual meaning), “code of conduct”, “code of practice”, “policy”. Many considerations about standards seem to touch these other concepts as well. All of them could perhaps be seen as formulations or expressions, guiding or governing interaction between people.

And if there is much common ground between the development of all of these kinds of formulation, then learning about standardization might well be adapted to learn knowledge, skills, competence, attitudes and values that are useful in many walks of life, but particularly in the emerging economy of open co-operation and collaboration on the commons.