The full but mixed audience meant that this event was partly introductory, giving good revision, but going on to some interesting ideas around open linked data. What I was most looking for, leads on linked personal data, wasn’t covered, but it was useful nevertheless.

Nigel Shadbolt, the first keynote speaker, has the co-distinction with Sir Tim B-L of advising for data.gov.uk, and naturally he talked about government linked data. It is great that so much information is being exposed from government sources. I asked him about the National Occupational Standards maintained by Sector Skills Councils, coordinated by the UK Commission on Employment and Skills, and I hope he will be able to advise on leverage points, as even the first steps of the linked data ladder, giving things dereferenceable URIs, would be a highly significant for skills and competences for use in conjunction with learning outcomes, job role competence specifications, and matching outcomes of learning to skills wanted for employment. (UKCES is sponsored by several government departments, though BIS is the lead sponsor and therefore would probably be our best point of contact.)

Crown Copyright information is to have a new, more open, licence, assumed and designed to help reuse. Nigel introduced two sites, enakting.org and sameAs.org, which featured in later presentations as well (both useful and new to me).

Antoine Isaac gave a good introduction to SKOS. I asked him later about applying SKOS to skill definitions, and he seemed to agree that some specialisation of skos:broader and skos:narrower was in order. He also encouraged me to bring the topic up on the SKOS mailing list, which I will do when ready. He seemed to (and Nigel Shadbolt certainly did) imply that linked data meant using RDF/XML as the vehicle — somewhat daunting if not actually dispiriting — but at the end it became apparent that Antoine at least regarded RDFa as equivalent to RDF/XML. The more popular- and commercial-minded participants and presenters seemed to favour RDFa, which left me wondering how in touch RDF/XML proponents are. Probably not that many people are aware that RDFa is currently being developed to be more friendly to people who have started with microformats, so some existing reading on RDFa might not yet be as persuasive as it could be. However, it was good to note that no one at this conference was advocating microformats. Microdata, on the other hand, seems to be an entirely unknown quantity. (Current discussions within the RDFa community suggest a possible cross-mapping.)

Richard Wallis brought the Birmingham origins of Talis (co-sponsors of the event) into a generally informative presentation reinforcing some points already made with interesting examples. His presentation is on slideshare under his id of “rjw”.

Steve Dale told us about the local government “Knowledge Hub“, a “big, bold and ambitious” project going live in February 2011. Again it is about public sector information, though this time perhaps as much for local government workers themselves (who may not even be aware of all the information held) as much as members of the public. Needless to say, none of this involves information about individual members of the public, though I did engage in some discussion around this. Seems that people still shy away from the area. My view would be that individuals have more to gain than to lose by having the infrastructure available for them easily to access information held about them from various sources, particularly in the public sector.

After a pleasant and plenteous lunch, Martin Hepp introduced the GoodRelations ontology, designed for representing the semantics of e-commerce, thus enabling much faster and more accurate matches of offers and requests. He reckons that a very large proportion of GDP — perhaps over 50% — can be accounted for as involved with commercial matchmaking, which becomes quite plausible when you consider that it must include marketing, advertising, etc. Hence it is clear that improvements here can have a huge positive effect on an economy. Martin was one of the explicit advocates of RDFa, and the systems he helps to facilitate use RDFa.

Then came the well-known-to-us Andy Powell (one of the very few I knew there) telling a well-illustrated “long and winding road” story of how Dublin Core has related to RDF, in the process trying to balance the enthusiasm of the Semantic Web evangelists against the cataloguing librarians who were not at all so sure. He introduced the amusing Southampton blog post describing a new Batman antihero, “the Modeller”, which I hadn’t seen before…

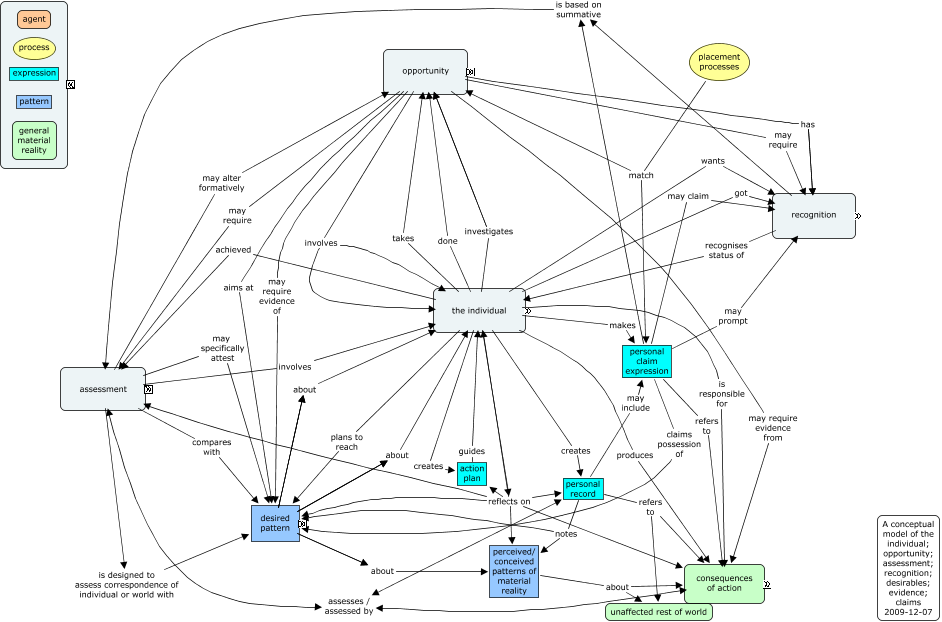

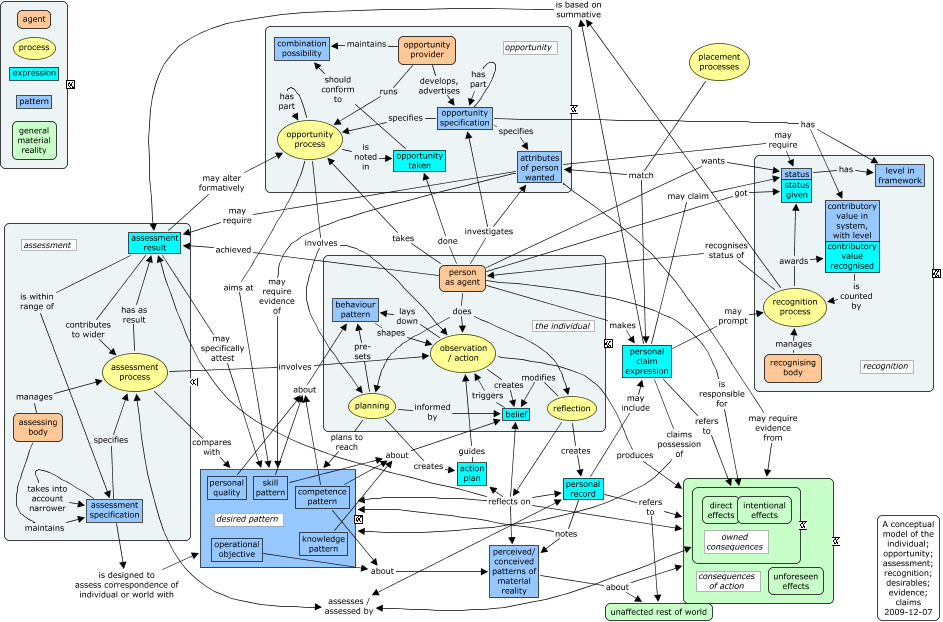

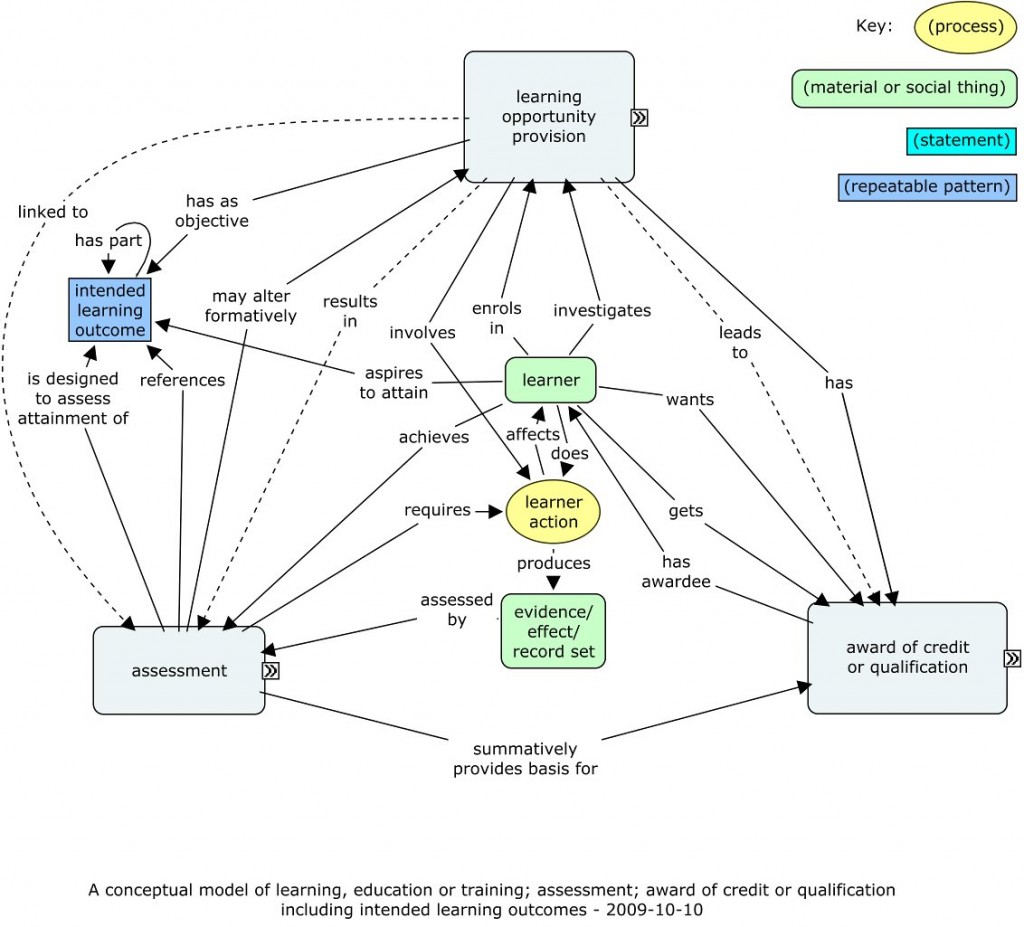

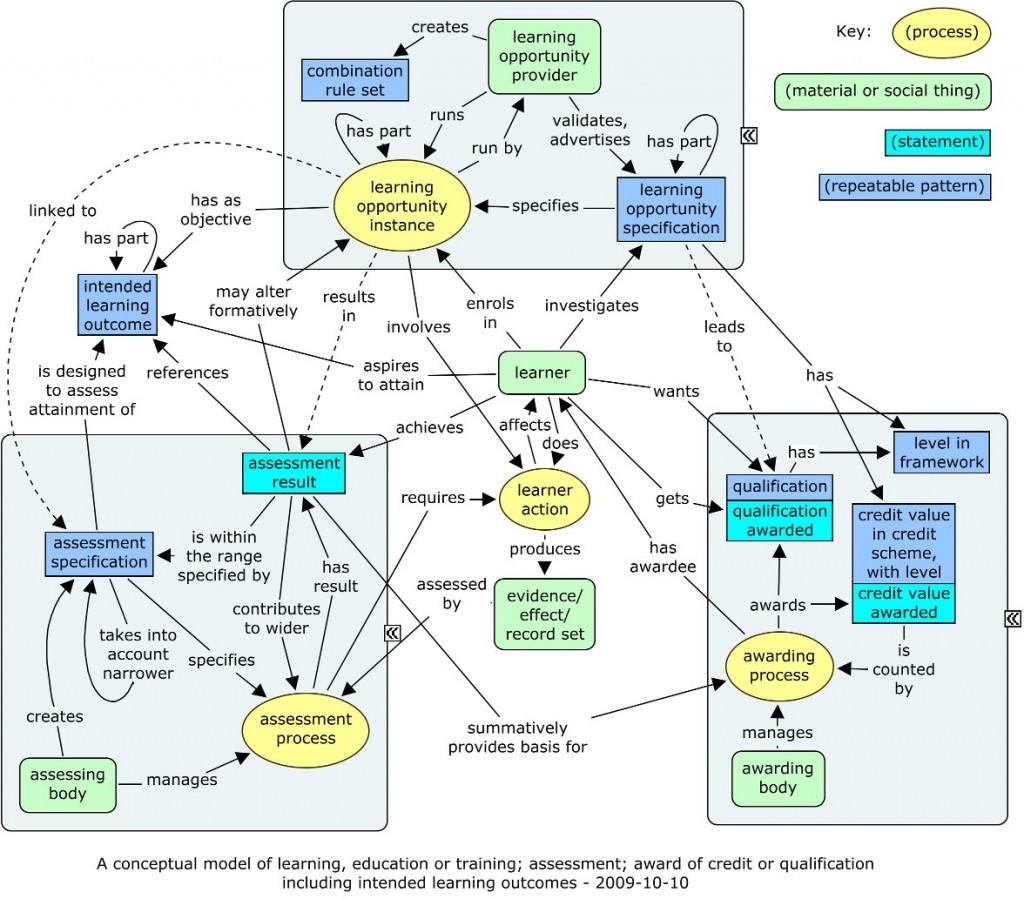

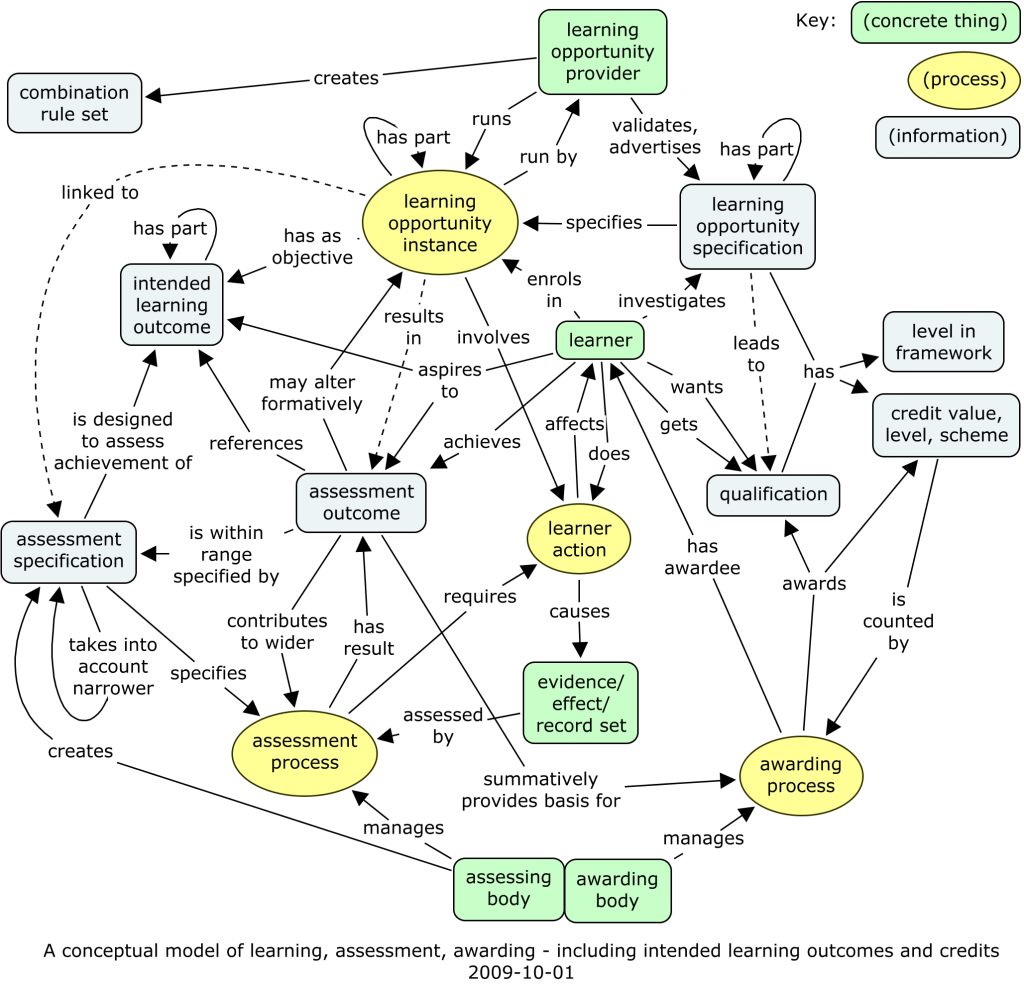

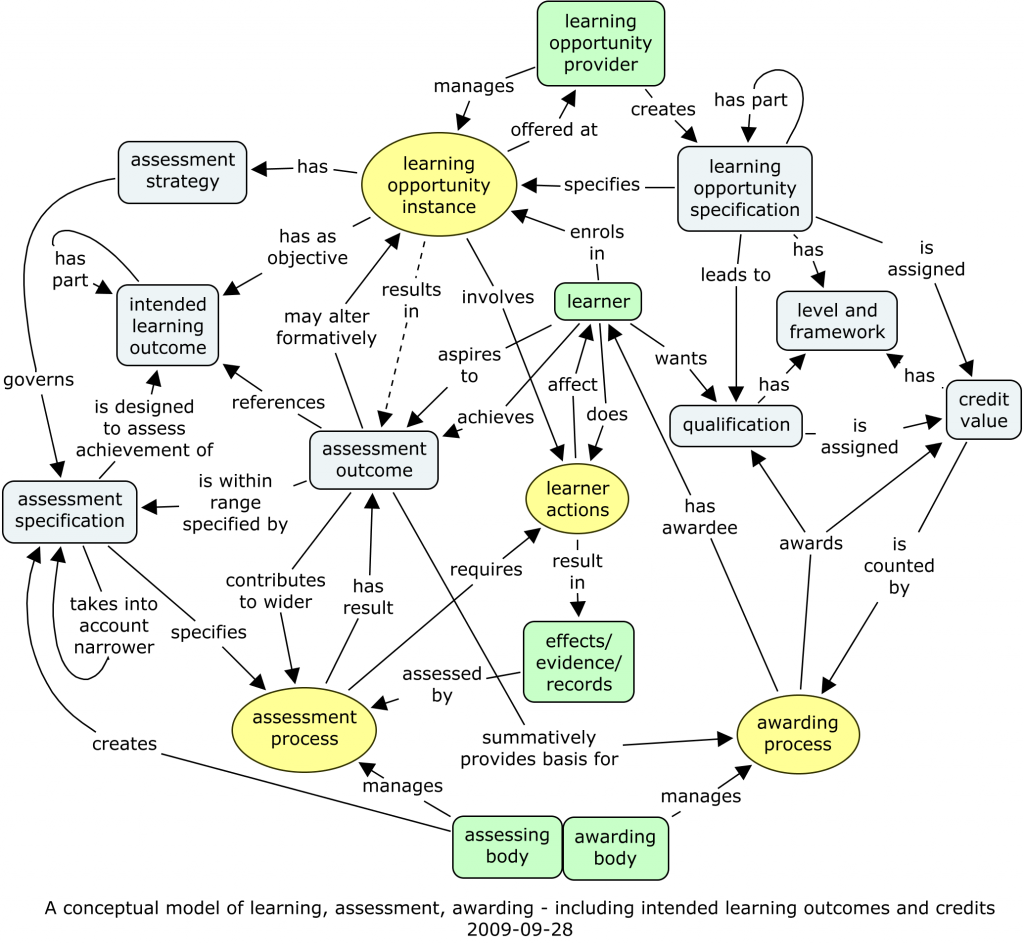

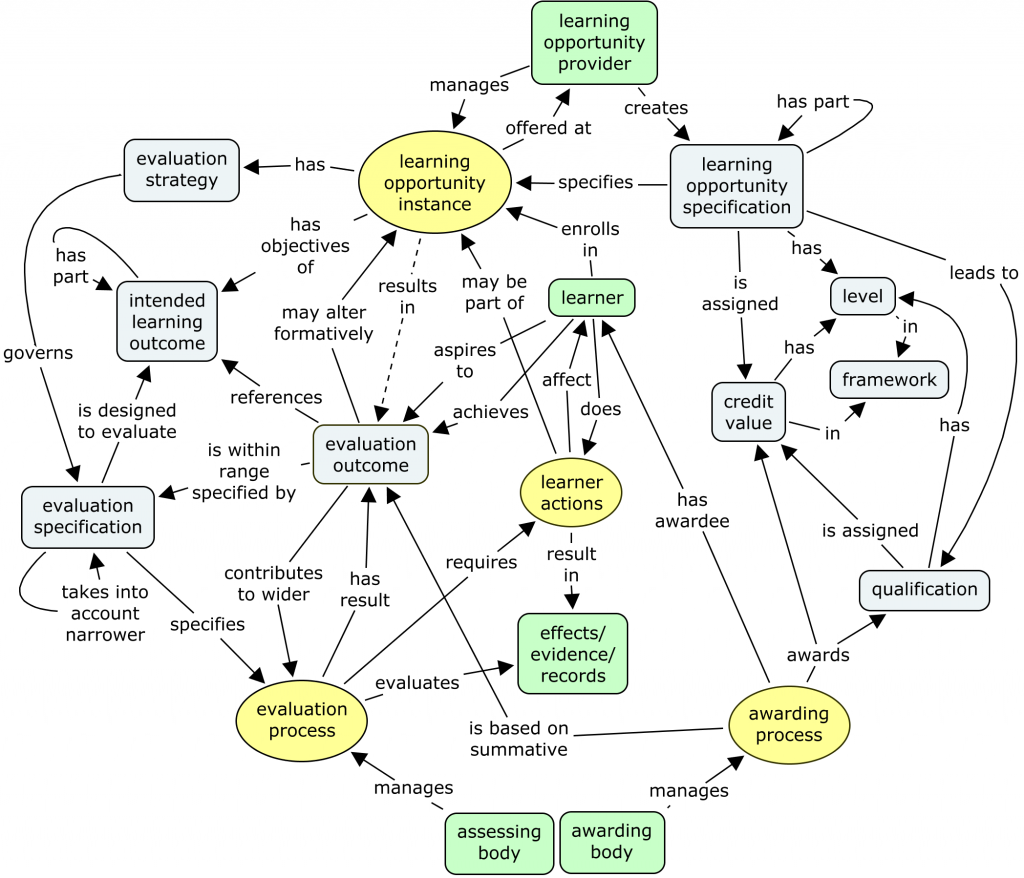

Challenges that he pointed out include the fact that modelling is hard, and that models have to gain recognition and consensus within a community before becoming useful. This fits in well with my recent emphasis on the processes supporting consensus in conceptual modelling, as a precursor to standardisation.

John Goodwin went into more detail about the Ordnance Survey’s “OpenData”, exposing for free the small-scale map geographical data of the country, though keeping the large-scale detail to sell. New to me. But some fascinating challenges came up for discussion. How does one relate, and keep track, of geographical entities that may both change their names, and have subtly different meanings in different contexts? “Hampshire” was used as an example (does it include the Isle of Wight, Bournemouth, or even Southampton?) Even more interestingly, he is looking at building up a vernacular gazetteer, for example to help emergency services locate places referred to by local people under the names they actually use.

The other co-sponsor of the event was punkt. netServices from Austria. Andreas Blumauer demonstrated their “PoolParty” system, which certainly looked clever enough, and includes a “corporate ontology” similar to the idea I was advocating for CETIS a while back, in connection with the topics that we have on our web site and blogs. Is it really that easy, I wondered?

The most esoteric presentation was reserved to the final spot. Bernard Vatant of Mondeca explained how there is more than the concept-centric SKOS to his ideal of linking data. Not just the Semantic Web, but the Semiotic Web… He would like to complement the representation of concepts with an explicit representation also of terms themselves. Give the terms their own URIs, make statements about them, don’t just include them as bare literals. Why exactly, I wondered, other than theoretical rigour, or the motive to include the discourse of semiotics (etc.)? If I had a few hours with him some time, I’d really like to bottom this out in conversation, partly to follow my bent towards relating to as many different conceptual starting points as I can.

The networking was valuable. As well as querying Nigel Shadbolt and Antoine Isaac, I caught up with some people I came across some time ago from Metataxis, asked some of the many BBC people there about skills and competences, and at least made one contact interested in linking personal data. (Colleagues are of course very welcome to ask me more while the memories are fresh.)