(18th in my logic of competence series)

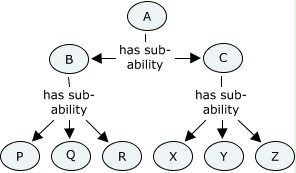

Having prepared the ground, I’m now going to address in more detail how levels of competence can best be represented, and the implications for the rest of representing competence structures. Levels can be represented similar to other competence concept definitions, but need different relationships.

I’ve written about how giving levels to competence reflects common usage, at least for competence concepts that are not entirely assessable, and that the labels commonly used for levels are not unique identifiers; about how defining levels of assessment fits into a competence structure; and lately about how defining levels is one approach to raising the assessability of competence concepts.

Later: shortly after first writing this, I put together the ideas on levels more coherently in a paper and a presentation for the COME-HR conference, Brussels.

Some new terms

Now, to take further this idea of raising assessability of concepts, it would be useful to define some new terms to do with assessability. It would be really good to know if anyone else has thought along this direction, and how their thoughts compare.

First, may we define a binarily assessable concept, or “binary” for short, as a concept typically formulated as something that a person either has or does not have, and where there is substantial agreement between assessors over whether any particular person actually has or does not have it. My understanding is that the majority of concepts used in NOSs are intended to be of this type.

Second, may we define a rankably assessable concept, or “rankable” for short, as a concept typically formulated as something a person may have to varying degrees, and where there is substantial agreement between assessors over whether two people have a similar amount of it, or who has more. IQ might be a rather old-fashioned and out-of-favour example of this. Speed and accuracy of performing given tasks would be another very common example (and widely used in TV shows), though that would be more applicable to simpler skills than occupational competence. Sports have many scales of this kind. On the occupational front, a rankable might be a concept where “better” means “more additional abilities added on”, while still remaining the same basic concept. Many complex tasks have a competence scale, where people start off knowing about it and being able to follow someone doing it, then perform the tasks in safe environments under supervision, working towards independent ability and mastery. In effect, what is happening here is that additional abilities are being added to the core of necessary understanding.

Last, may we define a unorderly assessable concept, or “unordered” for short, as any concept that is not binary or rankable, but still assessable. For it to remain assessable despite possible disagreement about who is better, there at least has to be substantial agreement between assessors about the evidence which would be relevant to an assessment of the ability of a person in this area. In these cases, assessors would tend to agree about each others’ judgements, though they might not come up with the same points. Multi-faceted abilities would be good examples: take management competence. I don’t think there is just one single accepted scale of managerial ability, as different managers are better or worse at different aspects of management. Communication skills (with no detailed definition of what is meant) might be another good example. Any vague competence-related concept that is reasonably meaningful and coherent might fall into this category. But it would probably not include concepts such as “nice person” where people would disagree even about what evidence would count in its support.

Defining level relationships

If you allow these new terms, definitions of level relationships can be more clearly expressed. The clearest and most obvious scenario is that levels can be defined as binaries related to rankables. Using an example from my previous post, success as a pop songwriter based on song sales/downloads is rankable, and we could define levels of success in that in terms of particular sales, hits in the top ten, etc. You could name the levels as you liked — for instance, “beginner songwriter”, “one hit songwriter”, “established songwriter”, “successful songwriter”, “top flight songwriter”. You would write the criteria for each level, and those criteria would be binary, allowing you to judge clearly which category would be attributed to a given songwriter. Of course, to recall, the inner logic of levels is that higher levels encompass lower levels. We could give the number 1 to beginner, up to number 5 for top flight.

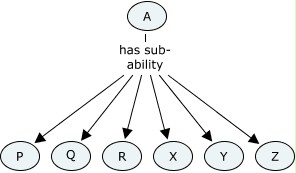

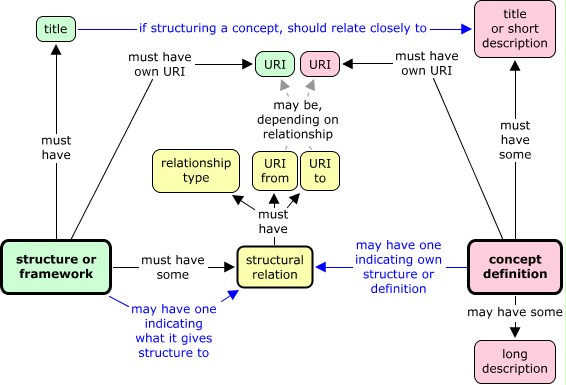

To start formalising this, we would need an identifier for the “pop songwriter” ability, and then to create identifiers for each defined level. Part of a pop songwriter competence framework could be the definitions, along with their identifiers, and then a representation of the level relationships. Each level relationship, as defined in the framework, would have the unlevelled ability identifier, the level identifier, the level number and the level label.

If we were to make an information model of a level definition/relationship as an independent entity, this would mean that it would include:

- the fact that this is a level relationship;

- the levelled, binary concept ID;

- the framework ID;

- the level number;

- the unlevelled, rankable concept ID;

- the level label.

If this is represented within a framework, the link to the containing framework is implicit, so might not show clearly. But the need for this should be clear if a level structure is represented separately.

As well as defining levels for a particular area like songwriting, it is possible similarly (as many actual level frameworks do) to define a set of generic levels that can apply to a range of rankable, or even unordered, concepts. This seems to me to be a good way of understanding what frameworks like the EQF do. Because there is no specific unlevelled concept in such a framework, we have to make inclusion of the unlevelled concept within the information model optional. The other thing that is optional is the level label. Many levels have labels as well as numbers, but not all. The number, however, though it is frequently left out from some level frameworks, is essential if the logic of ordering is to be present.

Level attribution

A key point that has been growing in conviction in me is that relationships for level attribution and level definition need to be treated separately. In this context, the word “attribution” suggests that a level is an attribute, either of a competence concept or of a person. It feels quite close to other sorts of categorisation.

Representing the attribution of levels is pretty straightforward. Whether levels are educational, professional, or developmental, they can be attributed to competence concepts, to individual claims and to requirements. Such an attribution can be expressed using the identifier of the competence concept, a relationship meaning “… is attributed the level …”, and an identifier for the level.

If we say that a certain well-defined and binarily assessable ability is at, say, EQF competence level 3, it is an aid to cross-referencing; an aid to locating that ability in comparison with other abilities that may be at the same or different levels.

A level can be attributed to:

- a separate competence concept definition;

- an ability item claimed by an individual;

- an ability item required in a job specification;

- a separate intended learning outcome for a course or course unit;

- a whole course unit;

- to a whole qualification, but care needs to be exercised, as many qualifications have components at mixed levels.

An assessment can result in the assessor or awarding body attributing an ability level to an individual in a particular area. This means that, in their judgement, that individual’s ability in the area is well described by the level descriptors.

Combining generic levels with areas of skill or competence

Let’s look more closely at combining generic levels with general areas of skill or competence, in such a way that the combination is more assessable. A good example of this is associated with the Europass Language Passport (ELP) that I mentioned in post 4. The Council of Europe’s “Common European Framework of Reference for Languages” (CEFRL), embodied in the ELP, make little sense without the addition of specific languages in which proficiency is assessed. Thus, the CEFRL’s “common reference levels” are not binarily assessable, just as “able to speak French” is not. The reference levels are designed to be independent of any particular language.

Thus, to represent a claim or a requirement for language proficiency, one needs both a language identifier and an identifier for the level. It would be very easy in practice to construct a URI identifier for each combination. The exact method of construction would need to be widely agreed, but as an example, we could define a URI for the CEFRL — e.g. http://example.eu/CEFRL/ — and then binary concept URIs expressing levels could be constructed something like this:

http://example.eu/CEFRL/language/mode/level#number

where “language” is replaced by the appropriate IETF language tag; “mode” is replaced by one of “listening”, “reading”, “spoken_interaction”, “spoken_production” or “writing” (or agreed equivalents, possibly in other languages); “level” is replaced by one of “basic_user”, “independent_user”, “proficient_user”, “A1″, “A2″, “B1″, “B2″, “C1″, “C2″; and “number” is replaced by, say, 10, 20, 30, 40 , 50 or 60 corresponding to A1 through to C2. (These numbers are not part of the CEFRL, but are needed for the formalisation proposed here.) A web service would be arranged where putting the URI into a browser (making an http request) would return a page with a description of the level and the language, plus other appropriate machine readable metadata, including links to components that are not binarily assessable in themselves. “Italian reading B1″ could be a short description, generated by formula, not separately, and a long description could also be generated automatically combining the descriptions of the language, reading, and the level criteria.

In principle, a similar approach could be taken for any other level system. The defining authority would define URIs for all separate binarily assessable abilities, and publish a full structure expressing how each one relates to each other one. Short descriptions of the combinations could simply combine the titles or short descriptions from each component. No new information is needed to combine a generic level with a specific area. With a new URI to represent the combination, a request for information about that combination can return information already available elsewhere about the generic level and the specific area. If a new URI for the combination is not defined, it is not possible to represent the combination formally. What one can do instead is to note a claim or a requirement for the generic level, and give the particular area in the description. This seems like a reasonable fall-back position.

Relating levels to optionality

Optionality was one of the less obvious features discussed previously, as it does not occur in NOSs. It’s informative to consider how optionality relates to levels.

I’m not certain about this, but I think we would want to say that if a definition has optional parts, it is not likely to be binarily assessable, and that levelled concepts are normally binarily assessable. A definition with optional parts is more likely to be rankable than binary, and it could even fail to be rankably assessable, rather being merely unordered. So, on the whole, defining levels should surely reduce, and ideally eliminate, optionality: levelled concepts should ideally have no optionality, or at least less than the “parent” unlevelled concept.

Proposals

So in conclusion here are my proposals for representing levels, as level-defining relations.

- Use of levels Use levels as one way of relating binarily assessable concepts to rankable ones.

- The framework Define a set of related levels together in a coherent framework. Give this framework a URI identifier of its own. The framework may or may not include definitions of the related unlevelled and levelled concepts.

- The unlevelled concept In cases of levels of a concept more general than the set of levels you are defining, ensure the unlevelled concept has one URI. In a generic framework, this may not be present.

- The levels Represent each level as a competence concept in its own right, complete with short and long descriptions, and a URI as identifier.

- Level numbering Give each level a number, such that higher levels have higher numbers. Sometimes consecutive numbers from 0 or 1 will work, but if you think judgements of personal ability may lie in between the levels you define, you may want to choose numbers that make good sense to people who will use the levels.

- Level labels If you are trying to represent levels where labels already exist in common usage, record these labels as part of the structured definition of the appropriate level. Sometimes these labels may look numeric, but (as with UK degree classes) the numbers may be the wrong way round, so they really are labels, not level numbers. Labels are optional: if a separate label is not defined, the level number is used as the label.

- The level relationships These should be represented explicitly as part of the framework. This can either be separately, or within a hierarchical structure.

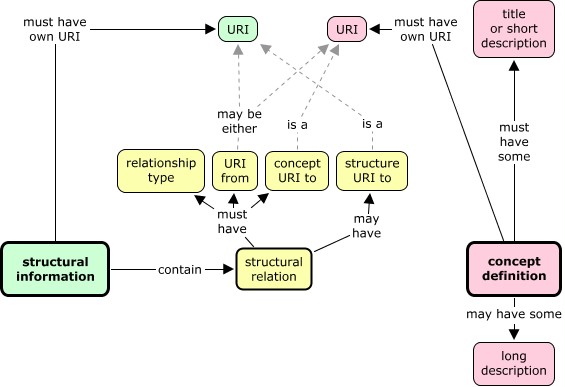

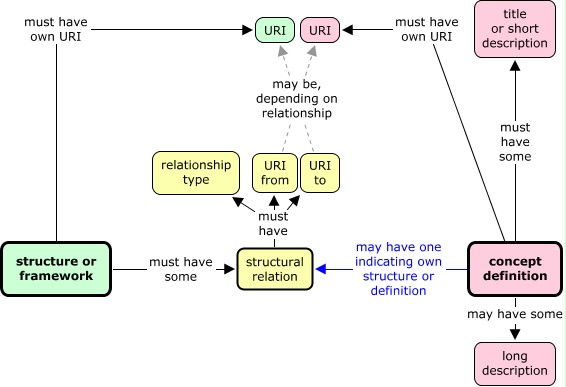

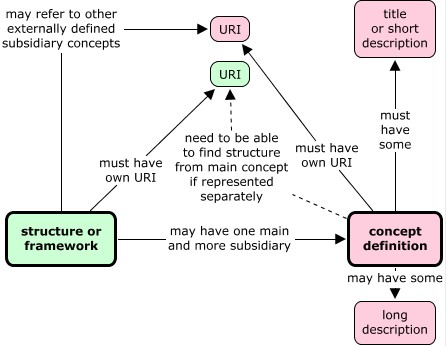

Representing level definitions allows me to add to the diagram that last appeared at the bottom of post 14, showing the idea of what should be there to represent levels. The diagram includes defining level relationships, but not yet attributing levels (which is more like categorising in other ways.)

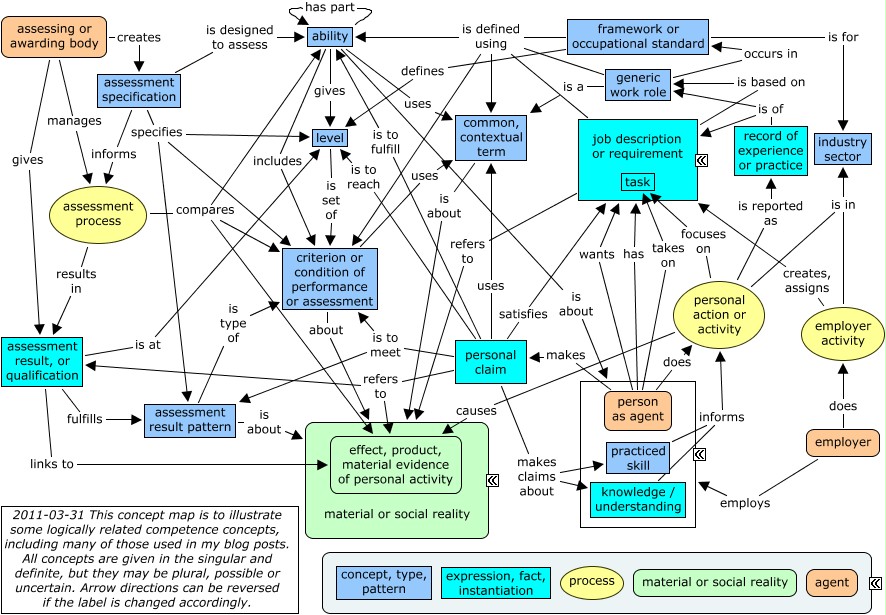

Later, I’ll go back to the overall concept map to see how the ideas that I’ve been developing in recent months fit in to the whole, and change the picture somewhat. But first, some long-delayed extra thoughts on specificity, questions and answers related to competence.