A very interesting event in Manchester on Monday (2014-10-20) called “Open : Data : Cooperation” was focused around the idea of “building a data cooperative”. The central idea was the cooperative management of personal information.

Related ideas have been going round for a long time. In 1999 I first came across a formulation of the idea of managing personal informaton in the book called “Net Worth“. Ten years ago I started talking about personal information brokerage with John Harrison, who has devoted years to this cause. In 2008, Michel Bauwens was writing about “The business case for a User Data Commons“.

A simple background story emerges from following the money. People spend money, whether their own or other people’s, and influence others in their spending of money. Knowing what people are ready to spend money on is valuable, because businesses with something to sell can present their offerings at an opportune moment. Thus, information which might be relevant to anyone buying anything is valuable, and can be sold. Naturally, the more money is at stake, the higher the price of information relevant to that purchase. Some information about a person can be used in this way over and over again.

Given this, it should be possible for people themselves to profit from giving information about themselves. And in small ways, they already do: store cards give a little return for the information about your purchases. But once the information is gathered by someone else, it is open for sale to others. One worry is that, maybe in the future if not right away, that information might enable some “wrong” people to know what you are doing, when you don’t want them to know.

Can an individual manage all that information about themselves better, both to keep it out of the wrong hands, and to get a better price for it from those to whom it is entrusted? Maybe; but it looks like a daunting task. As individuals, we generally don’t bother. We give away information that looks trivial, perhaps, for very small benefits, and we lose control of it.

It’s a small step from these reflections to the idea of people grouping together, the better to control data about themselves. What they can’t practically do separately, there is a chance of doing collectively, with enough efficiencies of scale to make it worthwhile, financially as well as in terms of peace of mind. You could call such a grouping a “personal data cooperative” or a “personal information mutual”, or any of a range of similar names.

Compared with gathering and holding data about the public domain, personal information is much more challenging. There are the minefields of privacy law, such as the Data Protection Act in the UK.

In Manchester on Monday we had some interesting “lightning” talks (I gave one myself – here are the slides on Slideshare,) people wrote sticky notes on relevant topics they were concerned about, and there were six areas highlighted for discussion:

- security

- governance

- participation & inclusivity

- technical

- business model

- legislative

I joined the participation and the technical group discussions. Both fascinated me, in different ways.

The participation discussion led to thoughts about why people would join a cooperative to manage their personal data. They need specific motivation, which could come from the kind of close-knit networks that deal with particular interests. There are many examples of closely knit on-line groups around social or political campaigns, about specific medical issues, or other matters of shared personal concern. Groups of these kinds may well generate enough trust for people to share their personal information, but they are generally not large enough to have much commercial impact, so they might struggle to be sustainable as personal data co-ops. What if, somehow, a whole lot of these minority groups could get together in an umbrella organisation?

Curiously, this has much in common with my personal living situation in a cohousing project. Despite many people’s yearnings (if not cravings) for secure acceptance of their minority positions, to me it looks like our cohousing project is too large and diverse a group for any one “cause” to be a key part of the vision for everyone. What we realistically have is a kind of umbrella in which all these good and worthy causes may thrive. Low carbon footprints; local, organic food; veganism; renewable energy; they’re all here. All these interest groups live within a co-operative kind of structure, where the governance is as far as possible by consensus.

So, my current living situation has resonances with this “participation” – and my current work is highly relevant to the “technical” discussion. But the technical discussion proved to be hard!

If you take just one area of personal-related information, and manage to create a business model using that information, the technicalities start to be conceivable.

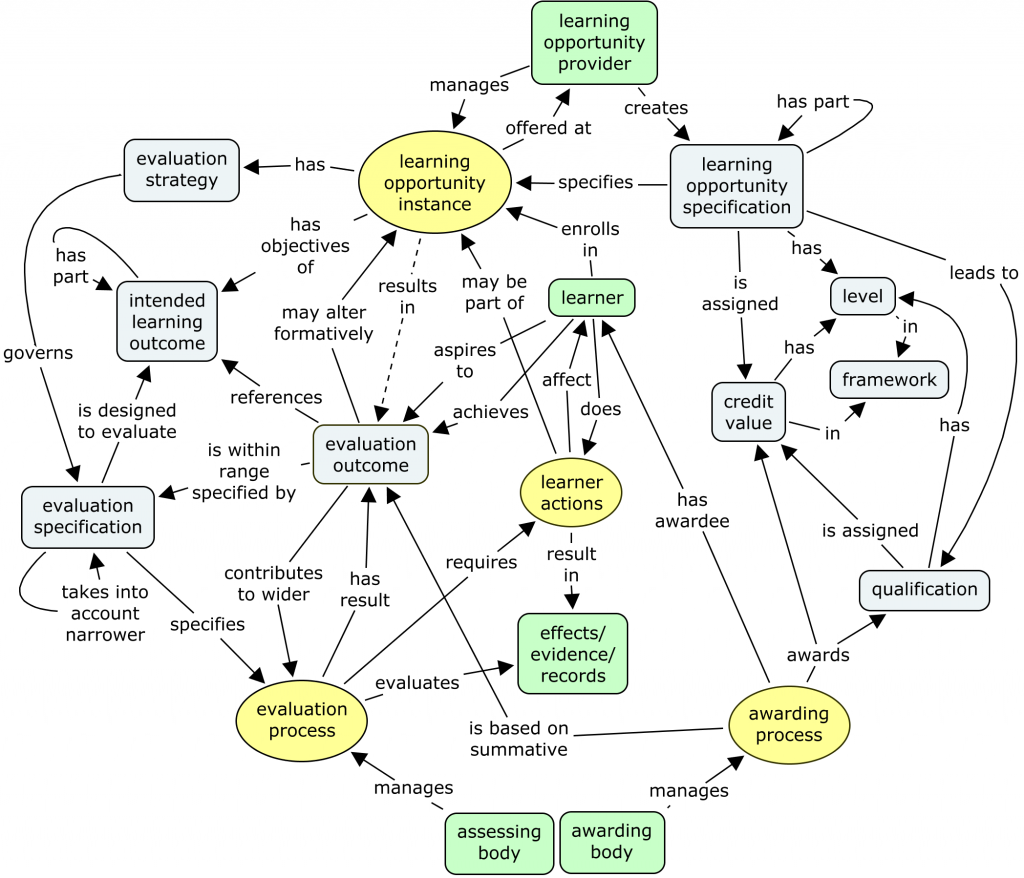

For instance, Cetis (particularly my colleague Scott Wilson) has been involved in the HEAR (Higher Education Achievement Report) for quite some time. Various large companies are interested in using the HEAR for recruiting graduates. Sure, that’s not a cooperative scenario, but it does illustrate a genuine business case for using personal data gathered from education. Then one can think about how that information is structured; how it is represented in some transferable format; how the APIs for fetching such information should work. There is definite progress in this direction for HEAR information in the UK – I was closely involved in the less established but wider European initiative around representing the Diploma Supplement, and more can be found under the heading European Learner Mobility.

While the HEAR is progressing towards viability, The “ecosystem” around learner information more widely is not very mature, so there are still questions about how effective our current technical formats are. I’ve been centrally involved in two efforts towards standardization: Leap2A and InLOC. Both have included discussion about the conceptual models, which has never been fully resolved.

More mature areas are more likely to have stable technical solutions. Less mature areas may not have any generally agreed conceptual, structural models for the data; there may be no established business models for generating revenues or profits; and there may be no standards specifically designed for the convenient representation of that kind of data. Generic standards like RDF can cover any linked data, but they are not necessarily convenient or elegant, and may or may not lead to workable practical applications.

Data sources mentioned at this meeting included:

- quantified self data

- that’s all about your physiological data, and possibly related information

- energy (or other utility) usage data

- coming from smart meters in the home

- purchasing data

- from store cards and online shops

- communication data

- perhaps from your mobile device

- learner information

- in conjunction with learning technology, as I introduced

I’m not clear how mature any of these particular areas are, but they all could play a part in a personal data co-op. And because of the diversity of this data, as well as its immaturity, there is little one can say in general about technical solutions.

What we could do would be to set out just a strategy for leading up to technical solutions. It might go something like this.

- Agree the scope of the data to be held.

- Work out a viable business model with that data.

- Devise models of the data that are, as far as possible, intuitively understandable to the various stakeholders.

- Consider feasible technical architectures within which this data would be used.

- Start considering APIs for services.

- Look at existing standards, including generic ones, to see whether any existing standard might suffice. If so, try using it, rather than inventing a new one.

- If there really isn’t anything else that works, get together a good, representative selection of stakeholders, with experience or skill in consensus standardization, and create your new standard.

It’s all a considerable challenge. We can’t ignore the technical issues, because ignoring them is likely to lead just to good ideas that don’t work in practice. On the other hand, solving the technical issues is far from the only challenge in personal data co-ops. Long experience with Cetis suggests that the technical issues are relatively easy, compared to the challenges of culture and habit.

Give up, then? No, to me the concept remains very attractive and worth working on. Collaboratively, of course!