A few weeks ago I had an opportunity to join a conversation between JISC and MIT OEIT (http://oeit.mit.edu/) to exchange information about current initiatives and possible collaborations. The general themes of the conversation were openness and sustainability. There was an agreed sense that, currently, “Open is the new educational tech” (Vijay). The areas of strategic interest, competencies, and knowledge of open institutes are now central to much educational development. JISC’s work in many diverse areas has contributed to the growth of openness both the successive programmes of work connected to repositories (including the cultivation of developer happiness) and more recently the JISC and HEA OER programme.

Vijay outlined some of the thinking that MIT OEIT are doing around innovation and sustainability outlining where they fit in that cycle and the limiting dependencies of innovation. In a four stage innovation cycle. MIT OEIT are mostly involved in the initial incubation/ development phase and the early implementation phase. They’re not in the business of running services but they need to ensure that their tools are designed and developed in ways which are congruous with sustainability. One key point in their analysis is that the limiting factor for innovation is not your organisational growth (whether the size of the project, design team, or facilities) but the growth of nascent surrounding communities in other parts of the value chain.

As a result, MIT have found that sustainability and embedding innovation isn’t just about more resources it’s about basic design choices and community development. Openness and open working allows the seeding of the wider community from the outset and allows a project to develop competencies and design skills in the wider community). This resonates with some of observations made by OSS Watch and Paul Walk. We then discussed the success of the Wookie widget work carried out by Scott Wilson (CETIS) and how that has successfully developed from a JISC project into an Apache Foundation incubator http://incubator.apache.org/wookie/.

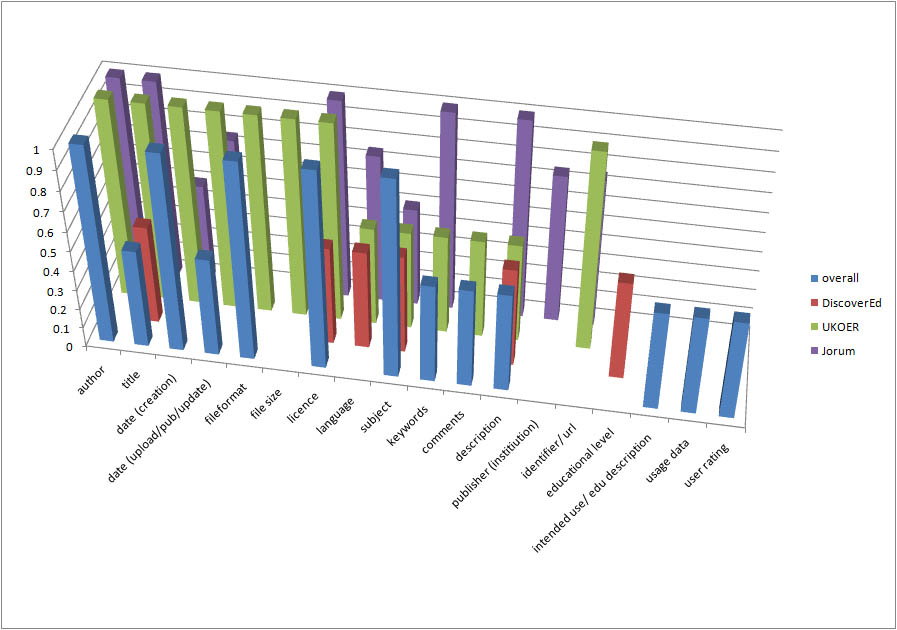

The conversation continued around the tech choices being made in the UKOER programme noting the strength in the diversity of approaches and tools that have been in use in the programme and the findings that appear to be emerging- there is no dominant software platform, choices about support for standards are being driven, in part, by the software platforms rather than a commitment to any standard. [I’ll blog more on this in January as the technical conversations with projects are completed]. We also noted upcoming work around RSS and deposit tools taking place both following on from the JISCRI deposit tools event and emerging from the UKOER programme [see Jorum’s discussion paper on RSS for ingest http://blogs.cetis.org.uk/lmc/2009/12/09/oer-rss-and-jorumopen/]

Brandon then highlighted the SpokenMedia project (http://spokenmedia.mit.edu/) creating tools to automatically transcribe video of lectures both for to enable better search and to make materials to be more accessible and scannable. The tools achieve up 60% base accuracy and are trainable up to 80% accuracy. MIT hope this will make lecture video significantly more browseable and are exploring the release of an api for this as an educational service.

We then discussed some projects working in areas that support bringing research data into curriculum. MIT have a series of projects in this area under the general name of STAR (http://web.mit.edu/star/) which provide suites of tools to use research data in the classroom. One successful implementation of this is STARBioGene allows Biology students to use research tools and materials as part of the core curriculum. Some of the STAR tools are desktop applications and some are cloud-based, many have been made open source.

The wider uptake of the project has contributed to the development of communities outside MIT who are using these tools – as such also it’s an example of growing the wider uptake community outlined in their innovation cycle. One consideration that it has raised about communities of use is that some of the visualisation tools require high performance computing (even if only needed in small bursts). The trend toward computationally intensive science education may create other questions of access beyond the license.

Another interesting tool that we discussed was the Folk Semantic Tool from COSL at Utah State University: on the one hand it’s another RSS aggregator for OERs, on the other, for users running Firefox and Greasemonkey it’s a plugin to add recommendations for OERs into any webpage (which runs off a single line of javascript). http://www.folksemantic.com/

MIT: M.S. Vijay Kumar & Brandon Muramatsu JISC: David Flanders, John Robertson (CETIS)