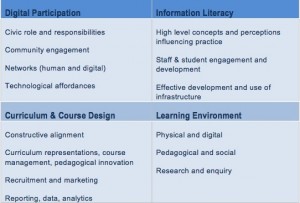

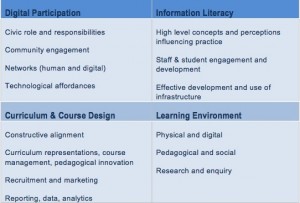

Continuing our discussions (introduction, part 2, part 3) around concepts of a Digital University, in this post we are going to explore the Curriculum and Course Design quadrant of our conceptual model.

To reiterate,the logic of our overall discussion starts with the macro concept of Digital Participation which provides the wider societal backdrop to educational development. Information Literacy enables digital participation and in educational institutions is supported by Learning Environments which are themselves constantly evolving. All of this has significant implications for Curriculum and Course Design.

Observant readers will have noticed that we have “skipped” a quadrant. However this is more down to my lack of writing the learning environment section, and Bill having completed this section first  However, we hope that this does actually illustrate the iterative and cyclical nature of the model, allowing for multiple entry points.

However, we hope that this does actually illustrate the iterative and cyclical nature of the model, allowing for multiple entry points.

MacNeill, Johnston Conceptual Matrix, 2012

Curriculum

Participation in university education, digital and otherwise, is normally based on people’s desire to learn by obtaining a degree, channelled in turn by their motivations e.g. school/college influences, improved career prospects, peer behaviour, family ambitions and the general social value ascribed to higher education. This approach includes adult returners taking Access routes, postgraduates and a variety of people taking short courses and accessing other forms of engagement.

All of these diverse factors combine to define the full nature of curriculum in higher education and argue for a holistic view of curriculum embracing “ …content, pedagogy, process, diversity and varied connections to the wider social and economic agendas…” ( Johnston 2010, P111). Such a holistic view fits well to the aspect of participation in our matrix, since it encompasses not only actual participants, but potential participants as befits modern notions of lifelong and life wide learning, whilst also acknowledging the powerful social and political forces that canalize the nature and experience of higher education. These latter forces have been omnipresent over the last 30 years in the near universal assumption that the overriding point of higher education is to provide ‘human capital’ in pursuit of economic growth.

University recruitment and selection procedures are the gateway to participation in degree courses and on admission initiate student transition experiences, for example the First Year Experience (FYE). Under present conditions, with degrees mainly shaped by disciplinary divisions, subject choice is the primary curriculum question posed by universities, with all other motivations and experiences constellated around the associated disciplinary differences in academic traditions, culture, departmental priority, pedagogy and choice of content. Other candidates for inclusion – employability skills, information literacy, even ethics and epistemological development have tended to be clearly subordinate to the power of disciplinary teaching.

Course Design

Despite 30 years of technological changes, the appearance of new disciplines, and mass enrolments, the popular image of a university degree ‘course’ has remained remarkably stable. Viewed from above we might see thousands of people entering buildings (some medieval, some Victorian, some modern), wherein they ‘become’ students, organized into classes/years of study and coming under the tutelage of subject-expert lecturers. Lectures, tutorials and labs, albeit larger and more technologically enhanced, can look much as they would have done in our grandparent’s day. Assuming our grandparents participated of course.

Looking at degrees in this rather superficial way, we could be accused of straying into the territory recently criticized by Michael Gove, whose attacks on ‘Victorian’ classrooms and demands for change and ‘updating’ of learning via computers and computer science have been widely reported and critiqued.

Our contention is that Gove and others like him have fallen into the trap of focussing on some of the contingent, surface features of daily activity in education and mistaken them for a ‘course’. Improvement in this universe is typically assumed to involve adoption of the latest technology linked to more ‘efficient’ practices. John Biggs (2007) has provided a popular alternative account of what constitutes a good university education by coining the notion of ‘constructive alignment’, which combines key general structural elements of a course – learning objectives, teaching methods, assessment practices and overall evaluation – with advocacy of a form of teaching for learning, distilled here as ‘social constructivism’. This form of learning emphasises the necessity of students learning by constructing meaning from their interactions with knowledge, and other learners, as opposed to simply soaking up new information, like so many inert, individual sponges. In this view, improving education is more complex and complicated than any uni-dimensional technological innovation and involves the alignment of all facets of course design in order to entail advanced learning. Debate is often focussed by terms like: active learning; inquiry based learning etc. accompanied by trends such as in-depth research and development of specific course dimensions such as assessment in particular.

Whist one can debate Biggs’ approach, and we assume some of you will, his work has been influential in university educational development, lecturer education and quality enhancement over several decades. From our perspective, his approach is useful in highlighting the critical importance of treating course design (and re-design) as the key strategic unit of analysis, activity and management in improving the higher education curriculum, as opposed to the more popular belief that it is the academic qualifications and classroom behaviour of lecturers or the adoption of particular technologies, for example, which count most. The current JISC funded Institutional Approaches to Curriculum Design Programme is providing another level of insight into the multiple aspects of curriculum design.

Connections & Questions

Chaining back through our model/matrix, we can now assert:

1. That strategic and operational management of learning environment must be a function of course design/re-design and not separate specialist functions within university organizations. This means engaging all stakeholders in the ongoing re-design of all courses to an agreed plan of curriculum renovation.

2. That education for information literacy must be entailed in the learning experiences of all students (and staff) as part of the curriculum and must be grounded in modern views of the field. Which is precisely what JISC is encouraging and supporting through its current Developing Digital Literacies Programme.

3. That participation in all its variety and possibility is a much more significant matter than simple selection/recruitment of suitably qualified people to existing degree course offerings. The nature of a university’s social engagement is exposed by the extent to which the full range of possible engagements and forms of participation are taken into account. For example is a given university’s strategy for participation mainly driven by the human capital/economic growth rationale of higher education, or are there additional/ alternative values enacted?

As ever, we’d appreciate any thoughts, questions and feedback you have in the comments.

*Part 2

*Part 3

*