Earlier this year I presented at conference at the University of Southampton, and I was really impressed by the presentations, and work, of the students who were there, as I reflected in this blog post. The University is really pushing ahead in terms of providing real engagement opportunities for students with its Digital Champions project, and now the eLanguages Research and Development group have released their Digital Literacies Toolkit.

Category Archives: oer

Open Scotland Report and Actions

“Open Policies can develop Scotland’s unique education offering, support social inclusion and inter-institutional collaboration and sharing and enhance quality and sustainability.”

This was the starting point for discussions at the Open Scotland Summit at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, which brought together senior representatives from a wide range of Scottish education institutions, organisations and agencies to discuss open education policy for Scotland. Facilitated by Jisc Cetis, in collaboration with SQA, Jisc RSC Scotland and the ALT Scotland SIG, Open Scotland provided senior managers, policy makers and key thinkers with an opportunity to explore shared strategic priorities and scope collaborative activities to encourage the development of open education policies and practices to benefit the Scottish education sector as a whole.[...]

Open Scotland, the twitter story

Yesterday Cetis, in collaboration with SQA, ALT-Scotland and the Jisc RSC Scotland hosted the Open Scotland Summit. The event, brought together senior managers, policy makers and key thinkers, will provide an opportunity for critical reflection on the national and global impact of open education (see Lorna’s blog post for more information and background to the event) . [...]

The Benefits of Open

The following paper was produced to act as a background briefing to the Open Scotland Summit , which Cetis is facilitating in collaboration with SQA, Jisc RSC Scotland and the ALT Scotland SIG. The Benefits of Open draws together and summarises key documents and publications relating to all aspects of openness in education. The paper covers Open Educational Resources, Massive Open Online Courses, Open Source Software, Open Data, Open Access and Open Badges.

The Benefits of Open briefing paper can be downloaded from the Cetis website here: http://publications.cetis.org.uk/2013/834.

Such is the rapid pace of change in terms of open education research and development that several relevant new papers have been published since this briefing paper was completed less than a fortnight ago. The following recent outputs are likely to be of particular interest and significance to those with an interest in open education policy and practice, both in Scotland and internationally. [..]

ALT Scotland SIG Meeting

The ALT Scotland SIG, which both Martin Hawksey and I are involved in, is holding a meeting this week on Thursday the 20th at Glasgow Caledonian University from 10.30 – 15.30. Registration for the event is now closed, however there are still a few places available so if you would like to come along please drop Linda Creanor a mail at l.creanor@gcu.ac.uk.

The agenda is as follows:[..]

What do FutureLearn’s Terms and Conditions say about open content?

ETA If you want to review yesterday’s twitter discussion about FutureLearn’s Terms and Conditions, Martin Hawksey has now set up one of his fabulous TAGSExplorer twitter archives here.

The appearance of FutureLearn’s new website caused considerable discussion on twitter this morning. Once everyone had got over the shock of the website’s eye-watering colour scheme, attention turned to FurtureLearn’s depressingly draconian Terms and Conditions, which were disected in forensic detail by several commentators who know more than a thing or two about licensing and open educational content. I’m not going to attempt to summarise all the legal issues, ambiguities and inconsistencies that others have spotted, but I do want to highlight what the Terms and Conditions say about educational content. You can read FutureLearn’s full Terms and Conditions here but the salient points to note in relation to content licensing are:

All FutureLearn’s content and Online Courses, are the property of FutureLearn and/or its affiliates or its or their licensors and are protected by copyright, patent and/or other proprietary intellectual property rights under the laws of England and other countries.

– Fair enough, I guess.

Users may not copy, sell, display, reproduce, publish, modify, create derivative works from, transfer, distribute or otherwise commercially exploit in any manner the FutureLearn Site, Online Courses, or any Content.

– If content can not be reproduced, modified or transferred then clearly it can not be reused, therefore it is not open.

Future Learn grants users access to their content under the term of the Creative Commons Attribution – No Derivatices – Non Commerical 3.0 licence.

– Again, use of the most restrictive Creative Commons licence means that FutureLearn content cannot be modified and reused in other contexts, therefore it is not open in any meaningful sense of the word.

Any content created by users and uploaded to FutureLearn will be owned by the user who retains the rights to their content, but by doing so, users grant FutureLearn “an irrevocable, worldwide, perpetual, royalty-free and non-exclusive licence to use, distribute, reproduce, modify, adapt, publicly perform and publicly display such User Content on the FutureLearn Site and/or in the Online Courses or otherwise exploit the User Content, with the right to sublicense such rights (to multiple tiers), for any purpose (including for any commercial purpose).”

- Unless that content happens to be subtitles, captions or translations of FutureLearn content….

FutureLearn may on occasion ask users to produce subtitles and translations of content in which case the same rights apply, but, and it’s a big but, in the case of captions and translations “you agree that the licence granted to FutureLearn above shall be exclusive.”

So there you have it, FutureLearn content will not be open educational resources in any real sense. I can’t say I’m surprised by FutureLearn’s Terms and Conditions and the approach they have taken to licensing educational content, but I am more than a little disappointed. Many colleagues have commented previously that the relationship between MOOCs and OERs is problematic, now it seems to have hit the skids altogether. I suppose I have to acknowledge that FutureLearn press releases have never said anything about the actual content of their courses being open, but I did hope rather naively that as the Open University have been at the forefront of OER initiatives in the UK, FutureLearn would buck the trend and take a similarly enlightened approach to their content. For the record, the Open University licenses their OpenLearn content under the more permissive Creative Commons ‘Attribution-Non-Commercial-Share-Alike’ licence. You can see the OpenLearn Intellectual Property FAQ here.

As time passes, I can’t help thinking that the approaches to content licensing taken by the UKOER Programmes are starting to look increasingly radical… Anyone remember those heady days when universities were releasing their educational content under CC BY licence? Was it all just a dream?

ebooks 2013

Every year for the past dozen or so years the Department of Information Sciences at UCL have organised a meeting on ebooks. I’ve only been to one of them before, two or three years ago, when the big issues were around what publishers’ DRM requirements for ebooks meant for libraries. I came away from that musing on what the web would look like if it had been designed by publishers and librarians (imagine questions like: “when you lend out our web page, how will you know that the person looking at the screen is a member of your library?”…). So I wasn’t sure what to expect when I decided to go to this year’s meeting. It turned out to be far more interesting than I had hoped, I latched on to three themes of particular interest to me: changing paradigms (what is an ebook?), eTextBooks and discovery.

Changing paradigms

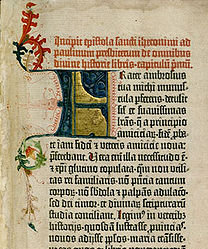

With the earliest printed books, or incunabula, such as the Gutenberg Bible, printers sought to mimic the hand written manuscripts with which 15th cent scholars were familiar; in much the same way as publishers now seek to replicate printed books as ebooks.

We need to treat digital content as offering new possibilities and requiring new ways of working. This might be uncomfortable for publishers (some more than others) and there was some discussion about how we cannot assume that all students will naturally see the advantages, especially if they have mostly encountered problematic content that presents little that could not be put on paper but is encumbered with DRM to the point that it is questionable as to whether they really own the book. But there is potential as well as resistance. Of course there can be more interesting, more interactive content–Will Russell of the Royal Society of Chemistry described how they have been publishing to mobile devices, with tools such as Chem Goggles that will recognise a chemical structure and display information about the chemical. More radically, there can also be new business models: Lorraine suggested Institutions could become publishers of their own teaching content, and later in the day Caren Milloy, also of Jisc Collections, and Brian Hole of Ubiquity Press pointed to the possibilities of open access scholarly publishing.

Caren’s work with the OAPEN Library is worth looking through for useful information relating to quality assurance in open monograms such as notifying readers of updates or errata. Caren also talked about the difficulties in advertising that a free online version of a resource is available when much of the dissemination and discovery ecosystem (you know, Amazon, Google…) is geared around selling stuff, difficulties that work with EDitEUR on the ONIX metadata scheme will hopefully address soon.

Brian described how Ubiquity Press can publish open access ebooks by driving down costs and being transparent about what they charge for. They work from XML source, created overseas, from which they can publish in various formats including print on demand, and explore economies of scale by working with university presses, resulting in a charge to the author (or their funders) of about £150 for a chapter assuming there is nothing to complex in that chapter.

eTextBooks

All through the day there were mentions of eTextBooks, starting again with Lorraine who highlighted the paperless medic and how his quest to work only with digital resources is complicated by the non-articulation of the numerous systems he has to use. When she said that what he wanted was all his content (ebooks, lecture handouts, his own notes etc.) on the same platform, integrated with knowledge about when and where he had to be for lectures and when he had exams, I really started to wonder how much functionality can you put into an eContent platform before it really becomes a single-person content-oriented VLE. And when you add in the ability to share notes with the social and communication capability of most mobile devices, what then do you have?

A couple of presentations addressed eTextBooks directly, from a commercial point of view. Jenni Evans spoke about Vital Source and Andrejs Alferovs about Kortext both of which are in the business of working with institutions distributing online textbooks to students. Both seem to have a good grasp of what students want, which I think should be useful requirements to feed into eTextBook standardization efforts such as eTernity, these include:

- ability to print

- offline access

- availability across multiple devices

- reliable access under load

- integration with VLE

- integration with syllabus/curriculum

- epub3 interactive content

- long term access

- ability for student to highlight/annotate text and share this with chosen friends

- ability to search text and annotations

Discovery

There was also a theme of resource discovery running through the day, and I have already mentioned in passing that this referenced Google and Amazon, but also social media. Nick Canty spoke about a survey of library use of social media, I thought it interesting that there seemed to be some sophisticated use of the immediacy of Twitter to direct people to more permanent content, e.g. to engagement on Facebook or the library website.

Both Richard Wallis of OCLC and Robert Faber of OUP emphasized that users tend to use Google to search and gave figures for how much of the access to library catalogue pages came direct from Google and other external systems, not from their own catalogue search interface. For example the Biblioteque Nationale de France found that 80% of access to their catalogue pages cam directly from web search engines not catalogue searches, and Robert gave similar figures for access to Oxford Journals. The immediate consequence of this is that if most people are trying to find content using external systems then you need to make sure that at least some (as much as possible, in fact) of your content is visible to them–this feeds in to arguments about how open access helps solve discoverability problems. But Richard went further, he spoke about how the metadata describing the resources needs to be in a language that Google/Bing/Yahoo understand, and that language is schema.org. He did a very good job distinguishing between the usefulness of specialist metadata schema for exchanging precise information between libraries or publishers, but when trying to pass general information to Google:

it’s no use using a language only you speak.

Richard went on to speak about the Google Knowledge graph and their “things not strings” approach facilitated by linked data. He urged libraries to stop copying text and to start linking, for example not to copy an author name from an authority file but to link to the entry in that file, in Eric Miller’s words to move from cataloguing to “catalinking”.

ebooks?

So was this really about ebooks? Probably not, and the point was made that over the years the name of the event has variously stressed ebooks and econtent and that over that time what is meant by “ebook” has changed. I must admit that for me there is something about the idea of a [e]book that I prefer over a “content aggregation” but if we use the term ebook, let’s use it acknowledging that the book of the future will be as different from what we have now as what we have now is from the medieval scroll.

Picture Credit

Scanned image of page of the Epistle of St Jerome in the Gutenberg bible taken from Wikipedia. No Copyright.

The thorny issue of MOOCs and OER

Along with the news that GCU and the Scottish College Development Network are developing guidelines for the creation and use of open educational resources, another Scottish news item caught my attention this week. Finally, after weeks of speculation, it was announced that the Universities of Glasgow and Strathclyde will join the FutureLearn partnership alongside the University of St Andrews which had previously signed up. You can read the press release here.

I can’t claim to have read every press release issued by FutureLearn but it’s telling, though not remotely surprising, that for all their apparent commitment to:

“…free, open, online courses from leading UK universities…”

- FutureLearn Press Release

“…removing the barriers to education by making learning more accessible…”

- Simon Nelson, FutureLearn, CEO

“…opening access to our learning to students around the world…”

- Colin Grant, Associate Deputy Principal at the University of Strathclyde

FutureLearn doesn’t appear to make any mention of using, creating or disseminating open educational resources. Although it’s rather disappointing, I can’t say that it’s particularly surprising. I haven’t got any statistics, but anecdotally, it seems that very few xMOOCs use or provide access to open educational resources. The relationship between MOOCs and OERs is problematic at best and non existent at worst. As Amber Thomas memorably commented at the Cetis13 conference “it’s like MOOCs stole OER’s girlfriend.” Perhaps I am being overly pesimistic about FutureLearn’s commitment to openness, after all, the initiative is being led by the Open University, an institution that has unquestionably been at the forefront of OER developments in the UK.

Of course St Andrews, Glasgow and Strathclyde aren’t the first Scottish universities to join the MOOC movement, the University of Edinburgh has already delivered six successful MOOCs in partnership with Coursera, including the eLearning and Digital Culture MOOC (#edcmooc) which my Cetis colleague Sheila MacNeill participated in and has blogged about extensively. Sheila recently presented about her experiences of being a MOOC student a the University of Southampton’s Digital Literacies Conference alongside #edcmooc tutor, and former CAPLE colleague, Dr Christine Sinclair, now with the University of Edinburgh. I wasn’t able to attend the event myself but I followed the tweet stream and was interested to note Sheila’s comments that the Edinburgh MSc module on digital cultures in more “open” than the Coursera MOOC on the same topic.

It didn’t take much googling to locate the eLearning and Digital Cultures MSc course blog which, sure enough, carries a CC-BY-NC-SA licence. I don’t know if this licence covers all the course materials but it certainly appears to be more open than the Coursera version of the same course and it’s very encouraging to see that the Edinburgh course tutors are continuing to support open access to their course materials at the same time as engaging with MOOCs. I wonder if the Scottish FutureLearn partners will show a similar commitment to opening access to their educational resources? I certainly hope so.

Small steps in the right direction

I was very encouraged by a couple of posts to the oer-discuss mailing list this week highlighting two Scottish institutions that are in the process of in developing guidelines and policies for the creation and use of open educational resources. The first post came from Marion Kelt, Senior Librarian at Glasgow Caledonian University, who shared the first draft of GCU’s Library Guidance on Open Educational Resources, which is based on guidelines developed and implemented by the University of Leeds.

GCU Library encourages all staff and student to create and publish OERs and the guidelines strongly suggest that the use and creation of OERs should be the default position of all schools, departments and services.

“Unless stated to the contrary, it is assumed that use, creation and publication of single units or small collections will be allowed. Where use, creation and publication are to be restricted, Schools, Departments and Services are encouraged to identify and communicate a rationale for restriction.”

The guidelines recommend that OERs should be licensed using the Creative Commons Attribution licence (CC-BY) and make it clear that it is the responsibility of individual staff and students to ensure they have the rights to publish their resources. GCU should be identified as the licensor and copyright holder and staff are encouraged to assert their moral rights to be properly acknowledged as the author of the resources.

The guideliens also recommend that GCU resources should be deposited in Jorum, and that audio or video based OER teaching resources should be deposited in the university’s multimedia repository, GCUStore.

Following Marion’s post to oer-discs I asked list members if they knew of any other Scottish F/HE institutions that were developing similar policies or guidelines. Jackie Graham of the Scottish College Development Network replied that they are also in the process of developing

“…a policy statement for the organisation, and a set of guidelines for staff on the use and sharing of OER. This work is being undertaken as part of the Re:Source initiative which aims to encourage and facilitate the greater open sharing of resources across the college sector in Scotland.”

Re:Source is a Jorum-powered window onto the Scottish FE community’s open content which launched in November 2012. The service uses the existing Jorum digital infrastructure, together with customised branding and interface, to providing access to a rich collection of content from Scotland’s Colleges.

It’s hugely encouraging to see Scottish universities and colleges taking steps to formulate coherent institutional OER guidelines and it’s even more encouraging that these guidelines acknowledge the beneficial role that institutional libraries and the Jorum national repository can play in supporting the creation, use and dissemination of open educational resources within institutions and across the sector.

In light of the forthcoming Open Scotland event that Cetis are running togther with SQA, Jisc RSC Scotland and ALT Scotland SIG, I’d be very interested to hear if any other Scottish colleges or universities are in the process of developing similar guidelines or policies for the creation or use of open educational resources, or the adoption of open educational practices more widely, so if anyone knows of any more examples I’d be very grateful if you could let me know.

Open Scotland

In collaboration with SQA, Jisc RSC Scotland and the ALT Scotland SIG, Cetis is hosting a one day

summit focused on open education policy for Scotland which will take place at the National Museum of Scotland at the end of June. The event, which will bring together senior managers, policy makers and key thinkers, will provide an opportunity for critical reflection on the national and global impact of open education. Open Scotland will also provide a forum for identifying shared strategic priorities and scoping further collaborative activities to work towards more integrated policies and practice and encourage greater openness in Scottish education.

The Open Scotland keynote will be presented by Cable Green, Creative Commons’ Director of Global Learning. Creative Commons are a non-profit organization whose free legal tools provide a global standard for enabling the open sharing of knowledge and creativity. Representatives of the Scottish Government, the National Library of Scotland, SQA, ALT Scotland, the University of Edinburgh, Glasgow Caledonian University, the Nordic OER Alliance, the EU Policies for OER Uptake Project, Kerson Associates, Jisc, Jorum, Jisc RSC Scotland and OSS Watch will be among those attending. A synthesis and report of the outputs of the summit will be disseminated publicly under open licence.

Open Scotland Overview

“A smarter Scotland is critical to delivering the Government’s Purpose of achieving sustainable economic growth. By making Scotland smarter, we will lay the foundations for the future wellbeing and achievement of our children and young people, increase skill levels across the population and better channel the outputs of our universities and colleges into sustainable wealth creation, especially participation, productivity and economic growth.”

http://www.scotland.gov.uk/About/Performance/scotPerforms/objectives/smarter

How can Scotland leverage the power of “open” to develop the nation’s unique education offering? Can openness promote strategic advantage while at the same time supporting social inclusion, inter-institutional collaboration and sharing, and create new opportunities for the next generation of teachers and learners? The Scottish Government’s ‘Scotland’s Digital Future’ strategy, published in 2011, sets out the steps that are required to ensure Scotland is well placed to take full advantage of all the economic, social and environmental opportunities offered by the digital age. However, whilst the Scottish Government has been active in advocating the adoption of open data policies and licences it has yet to articulate policies for open education and open educational resources. In March 2013, the Scottish Funding Council published a ‘Further and Higher Education ICT Strategy’ that builds on the Scottish further and higher education sectors’ culture of collaboration and the range of national shared services that are already in place, many of which are supported by Jisc, JANET UK and others. What kinds of open policies and practices can we develop and share across all sectors of Scottish education to help implement these strategies and move them forward?

Scotland has a proud and distinctive tradition of education, which is recognised internationally. The Curriculum for Excellence is transforming schools to better equip our children for the challenges of the 21st century. With our colleges and universities experiencing major changes in terms of structure, funding and access, Scotland’s colleges are opening up their educational content to the world through the new Re:Source OER repository. The University of Edinburgh have pioneered the delivery of MOOCs in Scotland, recently attracting over 300,000 students to six online courses, and Napier University is embracing open practice through their open 3E Framework for teaching with technology, which has been adopted by over 20 institutions globally. The Jisc RSC Scotland are making extensive use of the Mozilla Open Badge Infrastructure (OBI), which enables an open, standards-based way to issue digital recognition and accreditation. The Scottish Qualifications Authority is exploring how open badges can be built into the national qualifications system and the ICT Excellence Group, which is overseeing the re-development of the Scottish schools’ intranet GLOW, are also investigating their potential use

Elsewhere, the HEFCE funded UKOER Programme has been instrumental in stimulating the release of open educational resources and embedding open practice in English HE institutions. SURFNet in the Netherlands recently published their second ‘Trends Report on OER’, and a group of Nordic countries have launched the Nordic Alliance for OER. The UNESCO 2012 Paris Declaration called on governments to openly license publicly funded educational materials, and later that year the European Union issued a public consultation on “Opening up Education – a proposal for a European initiative” in advance of a new EU Initiative on “Opening up Education” expected to launch in mid-2013. Underpinning many of these developments is an increased acceptance and adoption of Creative Commons licences.

We are experiencing a period of unprecedented flux in all sectors of teaching and learning. For better or for worse, the advent of MOOCs has opened a public debate on the future direction of post-school education, though the balance of commercial opportunities and threats from the increased marketisation and commodification of education is still unclear.

Open Scotland is a one day summit facilitated by Jisc CETIS in collaboration with SQA, Jisc RSC Scotland and the ALT Scotland SIG. The event will provide an opportunity for key stakeholders to critically reflect on the national and global impact and opportunities of open education, provide a forum to identify shared strategic interests and work towards a more integrated Scottish approach to openness in education.

“UNESCO believes that universal access to high quality education is key to the building of peace, sustainable social and economic development, and intercultural dialogue. Open Educational Resources (OER) provide a strategic opportunity to improve the quality of education as well as facilitate policy dialogue, knowledge sharing and capacity building.”

http://www.unesco.org/new/en/communication-and-information/access-to-knowledge/open-educational-resources/