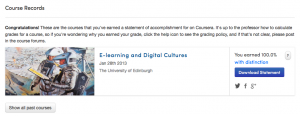

Oops, I did it again. I’ve now managed to complete another MOOC. Bringing my completion rate of to a grand total of 3 (the non completion number is quite a bit higher but more on that later). And I now have 6 badges from #oldsmooc and a certificate (or “statement of accomplishment”) from Coursera.

My #oldsmooc badges

Screenshot of Coursera record of achievement

But what do they actually mean? How, if ever, will/can I use these newly gained “achievements”?

Success and how it is measured continues to be one of the “known unknowns” for MOOCs. Debate (hype) on success is heightened by the now recognised and recorded high drop out rates. If “only” 3,000 registered users complete a MOOC then it must be failing, mustn’t it? If you don’t get the certificate/badge/whatever then you have failed. Well in one sense that might be true – if you take completion to equate with success. For a movement that is supposed to be revolutionising the (HE) system, the initial metrics some of the big xMOOCs are measuring and being measured by are pretty traditional. Some of the best known success of recent years have been college “drop outs’, so why not embrace that difference and the flexibility that MOOCs offer learners?

Well possibly because doing really new things and introducing new educational metrics is hard and even harder to sell to venture capitalists, who don’t really understand what is “broken” with education. Even for those who supposedly do understand education e.g. governments find any change to educational metrics (and in particular assessments) really hard to implement. In the UK we have recent examples of this with Michael Gove’s proposed changes to GSCEs and in Scotland the introduction of the Curriculum for Excellence has been a pretty fraught affair over the last five years.

At the recent #unitemooc seminar at Newcastle, Suzanne Hardy told us how “empowered” she felt by not submitting a final digital artefact for assessment. I suspect she was not alone. Suzanne is confident enough in her own ability not to need a certificate to validate her experience of participating in the course. Again I suspect she is not alone. From my own experience I have found it incredibly liberating to be able to sign up for courses at no risk (cost) and then equally have no guilt about dropping out. It would mark a significant sea change if there was widespread recognition that not completing a course didn’t automatically equate with failure.

I’ve spoken to a number of people in recent weeks about their experiences of #oldsmooc and #edcmooc and many of them have in their own words “given up”. But as discussion has gone on it is apparent that they have all gained something from even cursory participation either in terms of their own thinking about possible involvement in running a MOOC like course, or about realising that although MOOCs are free there is still the same time commitment required as with a paid course.

Of course I am very fortunate that I work and mix with a pretty well educated bunch of people, who are in the main part really interested in education, and are all well educated with all the recognised achievements of a traditional education. They are also digital literate and confident enough to navigate through the massive online social element of MOOCs, and they probably don’t need any more validation of their educational worth.

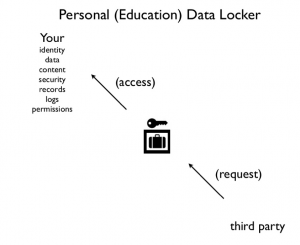

But what about everyone else? How do you start to make sense of the badges, certificates you may or may not collect? How can you control the way that you show these to potential employers/Universities as part of any application? Will they mean anything to those not familiar with MOOCs – which is actually the vast majority of the population. I know there are some developments in California in terms of trying to get some MOOCs accredited into the formal education system – but it’s very early stages.

Again based on my own experience, I was quite strategic in terms of the #edcmooc, I wrote a reflective blog post for each week which I was then able to incorporate into my final artefact. But actually the blog posts were of much more value to me than the final submission or indeed the certificate (tho I do like the spacemen). I have seem an upward trend in my readership, and more importantly I have had lots of comments, and ping backs. I’ve been able to combine the experience with my own practice.

Again I’m very fortunate in being able to do this. In so many ways my blog is my portfolio. Which brings me a very convoluted way to my point in this post. All this MOOC-ery has really started me thinking about e-portfolios. I don’t want to use the default Coursera profile page (partly because it does show the course I have taken and “not received a certificate” for) but more importantly it doesn’t allow me to incorporate other non Coursera courses, or my newly acquired badges. I want to control how I present myself. This relates quite a lot to some of the thoughts I’ve had about using Cloudworks and my own educational data. Ultimately I think what I’ve been alluding to there is also the development of a user controlled e-portfolio.

So I’m off to think a bit more about that for the #lak13 MOOC. Then Lorna Campbell is going to start my MOOC de-programming schedule. I hope to be MOOC free by Christmas.