I wanted to demo my meshup of a triplised version of CETIS’ PROD database with the impressive Linked Data Research Funding Explorer on the Linked Data meetup yesterday. I couldn’t find a good slot, and make my train home as well, so here’s a broad outline:

The data

The Department for Business Innovation and Skills (BIS) asked Talis if they could use the Linked Data Principles and practice demonstrated in their work with data.gov.uk to produce an application that would visualise some grant data. What popped out was a nice app with visuals by Iconomical, based on a couple of newly available data sets that sit on Talis’ own store for now.

The data concerns research investment in three disciplines, which are illustrated per project, by grant level and number of patents, as they changed over time and plotted on a map.

CETIS have PROD; a database of JISC projects, with a varying amount of information about the technologies they use, the programmes they were part of, and any cross links between them.

The goal

Simple: it just ought to be possible to plot the JISC projects alongside the advanced tech of the Research Funding Explorer. If not, than at least the data in PROD should be augmentable with the data that drives the Research Funding Explorer.

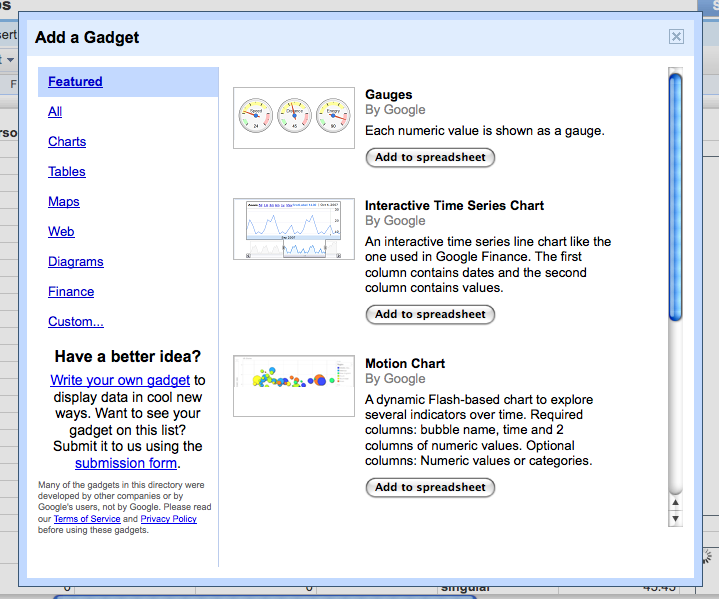

Tools

Anything I could get my hands on, chiefly:

- The D2R toolkit

- OpenLink’s Virtuoso platform and associated kit like their RDF browser

- Talis’ Platform

The recipe

For one, though PROD pushes out Description Of A Project (DOAP, an RDF vocabulary) files per project, it doesn’t quite make all of its contents available as linked data right now. The D2R toolkit was used to map (part of) the contents to known vocabs, and then make the contents of a copy of PROD available through a SPARQL interface. Bang, we’re on the linked data web. That was easy.

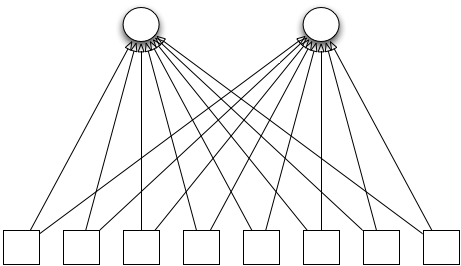

Since I don’t have access to the slick visualisation of the Research Funding Explorer, I’d have to settle for augmenting PROD’s data. This is useful for two reasons: 1) PROD has rather, erm, variable institutional names. Synching these with canonical names from a set that will go into data.gov.uk is very handy. 2) PROD doesn’t know much about geography, but Talis’ data set does.

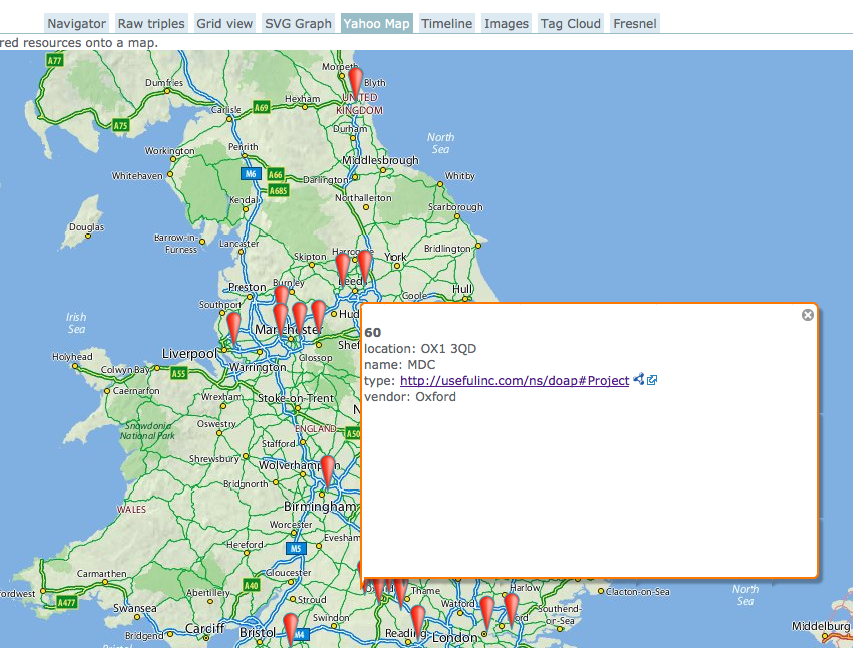

To make this work, I made a SPARQL query that grabs basic project data from PROD, and institutional names and locations from the Talis data set, and visualises the results.

Results

An excerpt of PROD project data, augmented with proper institutional names and geographic positions from Talis’ Research Grant Explorer, visualised in OpenLink RDF browser.

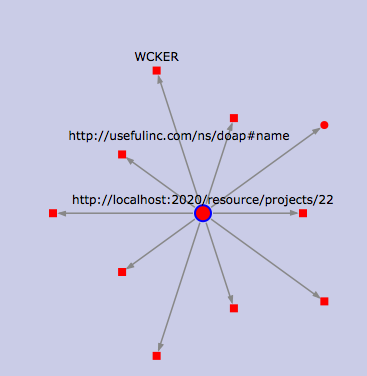

Zooming in on a project, this time to show the attributes of a single project. Still in OpenLink RDF browser.

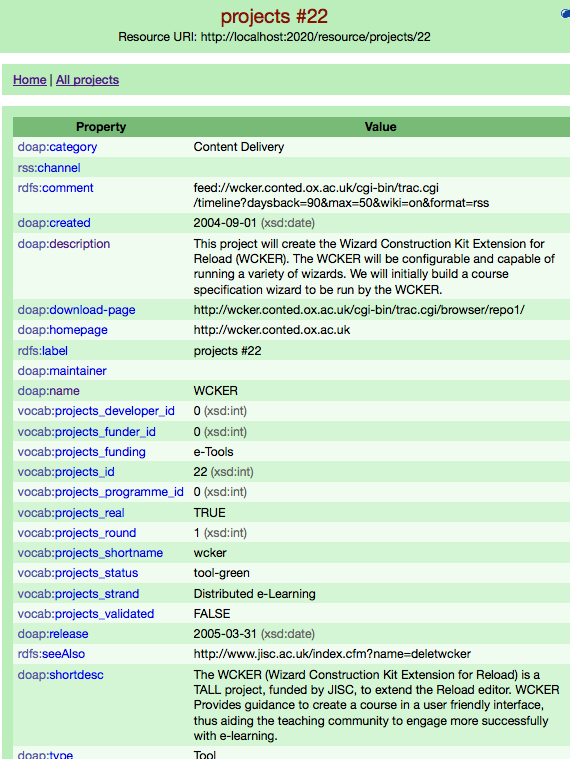

A project in D2R’s web interface; not shiny, but very useful.

From blagging a copy of the SQL tables from the live PROD database to the screen shots above took about two days. Opening up the live server straight to the web would have cut that time by more than half. If I’d have waited for the Research Grant Explorer data to be published at data.gov.uk, it’d have been a matter of about 45 minutes.

Lessons learned

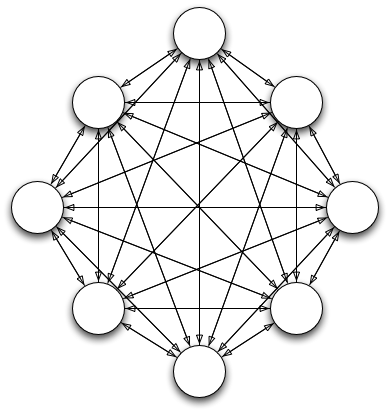

Opening up any old database as linked data is incredibly easy.

Cross-searching multiple independent linked data stores can be surprisingly difficult. This is why a single SPARQL endpoint across them all, such as the one presented by uberblic‘s Georgi Kobilarov yesterday, is interesting. There are many other good ways to tackle the problem too, but whichever approach you use, making your linked data available as simple big graphs per major class of thing (entity) in your dataset helps a lot. I was stymied somewhat by the fact that I wanted to make use of data that either wasn’t published properly yet (Talis’ research grant set), or wasn’t published at all (our own PROD triples).

A bit of judicious SPARQLing can alleviate a lot of inconsistent data problems. This is salient to a recent discussion on twitter around Brian Kelly’s Linked Data challenge. One conclusion was that it was difficult, because the data was ‘bad’. IMHO, this is the web, so data isn’t really bad, just permanently inconsistent and incomplete. If you’re willing to put in some effort when querying, a lot can be rectified. We, however, clearly need to clean up PROD’s data to make it easier on everyone.

SPARQL-panning for gold in multiple datastores (or even feeds or webpages) is way too much fun to seem like work. To me, anyway.

What’s next

What needs to happen is to make all the contents of PROD and related JISC project information available as proper linked data. I can see three stages for this:

- We clean up the PROD data a little more at source, and load it into the Data Incubator to polish and debate the database to triple mapping. Other meshups would also be much easier at that point.

- We properly publish PROD as linked data either on a cloud platform such as Talis’, or else directly from our own server via D2R or OpenLink Virtuoso. Simal would be another great possibility for an outright replacement of PROD, if it’s far enough along at that point.

- JISC publishes the public part of its project information as Linked Data, and PROD just augments (rather than replicates) it.